December is the time when we celebrate Finnish Independence. It is a curious national tradition of ours to commemorate the occasion by watching a film about a war we lost. There are now three different adaptations on Väinö Linna’s masterful novel Unknown Soldier (Tuntematon sotilas, 1954). Traditionally, Finns have been watching the oldest adaptation made in the 50s, but in recent years the old school film has been outclassed by a new adaptation made for independent Finland’s 100th anniversary.

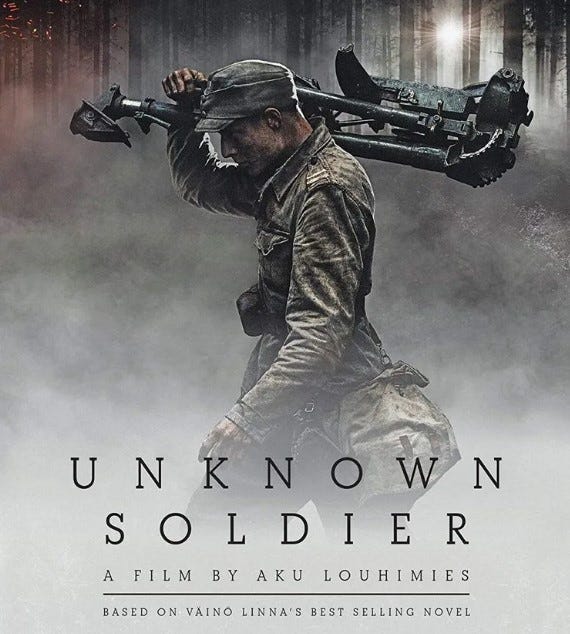

The new Unknown Soldier (2017) was directed by Aku Louhimies, and often reminds me of the Peter Jackson Lord of the Rings trilogy in making me wonder how on earth was such a based, high budget, politically incorrect piece of art ever possible in the miserable conditions of modern culture and modern film industry? It all feels like a miracle.

In this film the same actors whom you normally see debasing themselves in vulgar roles and vapid content suddenly rise to true pathos and excellence. Finnish film scripts tend to be cringe inducing and their direction workmanlike at best. But here both are brilliant and ambitious, with a clear vision maintained throughout. The uniquely large budget, intense and authentic battle scenes, and overall impeccable presentation fill out the rest, and we are left with something remarkable.

But most of all, the sense of national identity and cultural tradition that one thinks hopelessly lost are here resurrected and made poignant. It is no wonder the biggest newspapers and critics rated the film badly, and it was snubbed at the national film awards. But war veterans who saw the film in the theaters were reported to have wept profusely, remarking how perfectly it captured their experience.

In this piece I will go through some of the wisdom ingrained in the film. For the most part the film is very faithful to the novel, and where it deviates, it deviates wisely and with good taste. Nevertheless, I shall still be referring to the novel as well, when necessary.

Manhood

“War is the province of men”, says Éomer son of Éomund to his sister when battle approaches. This truth meets no denial in Unknown Soldier. Indeed, as part of the media campaign against the film, reporters complained about lack of representation, and asked why at least some of the characters from the novel weren’t “cast more creatively”, I.e. with women and black people. The following was the expression on the face of the director when a female journalist asked him in an interview: “Why didn’t you decide to show women fighting on the front line?”

As it is, the movie is a story both of Finnish manhood in particular, and of manhood in the more general, perennial sense. We follow the men of an ordinary machine gun company throughout the years 1941-1944, called the Continuation War in Finland. The different personalities of the company depict all the archetypes, and represent all the rungs of the socio-sexual hierarchy. We have the laconic guys (represented in good numbers, as these are Finns we are talking about), we have the funny guys, we have the natural born leaders, the trusty followers, the weaklings, the bullies, the men of faith and the materialists, the old-school leftists and the old-school rightists.

The two most central characters are Koskela and Rokka. Second Lieutenant Koskela as the leader of the company is the archetypal model of a good Finnish man. He’s quiet, he’s dutiful, he leads from the front, he’s in control of his emotions and reactions, he cares about his men, he’s humble, and success never makes him haughty. Koskela’s nobility reaches its height in his willingness to sacrifice his life for the sake of duty, and for the sake of his friends. This low-key Christian tenor of the story runs throughout, with Koskela being only one of the characters who typify it.

There are two Christian hymns that are sung in key moments of the story, one of them being Luther’s undying classic, “A Mighty Fortress is Our God”. In another key scene, the Lord’s Prayer is recited unflinchingly, as a reminder to the audience of the faith and hope that lived in the hearts of these men. This kind of reverence is simply astonishing in a modern film.

Corporal Rokka represents the side of Finnishness most foreigners are unfamiliar with. Rokka comes from the Eastern part of Finland, called Karelia. This is the area the Soviets had taken in the Winter War. The Karelians, then as now, are much more talkative, funny, outgoing and expressive than the “typical taciturn Finns”, who mainly come from a large tribe known as Tavastians. With the onset of the Continuation War, Finland takes back Karelia, and Rokka gets his lands back. For him, as with all the Karelians in real life, the war is particularly personal.

The movie presents him as the ideal family man that turns into a ruthless killer. The juxtaposition is done powerfully, both in terms of direction and acting. Each side of manhood is believably integrated in the same person. It never feels schizophrenic or disjointed. It’s the same Rokka we see in both aspects. The killing is represented as something he can naturally do, not as something that’s pathological or a sign of mental breakdown. After being a killer, Rokka just as quickly returns to being to family man and the funny guy of the company.

A third, more minor character again represents the Christian undertones of the story. When final defeat approaches and Soviet bombers strike hard against retreating Finns, Corporal Mäkilä leads a scared horse on a forest road. As bombs are striking left and right, he speaks to the animal reassuringly: “Let’s go now, take it easy. It’s not in man, it’s all in the hand of the Highest.” And right at that moment a bomb hits home, ending his life.

Many have taken this scene as proof that Linna’s story is cynical and denies Christian meaning from life. I, however, hold this scene as one of my favorites in the story, and see the matter quite differently. Is it not proof of the great poignancy of life that the bomb hits at that very moment? Just after God’s lordship is admitted, and humility expressed in the face of it? I believe Mäkilä’s death, in its superficial arbitrariness, is in truth among the most manful and meaningful in the whole story.

Womanhood

When the first nuggets of information on the film began to come out pre-release, there was much talk of how they were going to give women a larger role in the story. I of course took it as the reddest of red flags and adjusted my expectations accordingly. Imagine my surprise when I found out what they had done.

Yes, they had invented many new scenes with female characters that were only briefly mentioned in the novel. But all the invented content was traditionalist and reactionary! In addition, the writers had taken care to include politically incorrect topics from the novel that even the 1950s adaptation hadn’t dared to touch: namely how the female nurses on the front line became the willing concubines of the officers. Overall, it is as if the script writers had tried their hardest to be as anti-feminist as they possibly could.

However, most of the female content in the film is not at all sordid, but positively inspirational. The aforementioned Rokka has married the stereotypical “trad wife”, complete with the flower dress, the homestead and the wheat field. The imagery the film offers of his family life is deeply wholesome. The wife is always nervous about the dangers her husband returns to face after each holiday, but she never rebels, throws a tantrum, or challenges his authority. She submits to his leadership, and there is a sense of inherent pride amid all the worry. She knows has married a real man.

Another key character in the story is second lieutenant Kariluoto, who has a girl at home waiting for him. Before the end of the war they marry, again with a strikingly beautiful wedding scene that is sure to inspire many girls to dream about their own. What follows is the age old conversation. The young wife asks her husband not to go back to the front line. She knows he could ask for a re-assignment somewhere safer, and that he would gain it. The look she gives him is an astonishing combination of feminine persuasion and aching beauty on part of the actress. But Kariluoto says no. He chooses duty over love. And he dies. But again the film offers an optimistic message: despite death there is life, for the ideal bride is pregnant. Marriage is good even when shadowed by tragedy. Life defeats death.

Could you say no to those eyes?

The overall ethos of the movie is very chaste and marriage-centric. Where there is fornication, it is framed as something clearly abject or at the very least morally suspect. Examples include officers using the nurses for sexual pleasure and the nurses using the officers for affirmation and protection. And when the rank and file go whoring it’s always the sleaziest of the guys. There is one exception where an extramarital relationship is handled with a romantic air, but it too is shown to end in disappointment. Such respect given to chastity in a modern film is a sight to behold.

The picture the film offers of femininity is at the same time sorrowful and hopeful. Sorrowful because the same actresses who give these performances of chaste women with feminine demeanor (down to how they dress and hold themselves, how they gesture, how they speak with soft voices, how they look at men with modesty) behave completely differently in the cast interviews where they present themselves in the normal context of modernity. What we get to witness on the streets of current day Finland is the sad reverse of what is presented in the film.

But what makes me hopeful is how the 2017 film proves that femininity is clearly innate. A skillful director can draw it out, even from a dedicated feminist broken by modernity. Eternal femininity lives on, secretly, behind all the brainwashing and cultural programming. It cannot be truly erased, and the performances in the film constitute a proof. You don’t need to resurrect a woman from the 1950s to witness femininity. The film shows that even the typical modern girl (if given determined direction) is fully capable of it, perhaps unbeknownst to herself.

No wonder then that soon after the release of the film Louhimies got hit hard with the me too hammer, together with a well-planned and coordinated mass media smearing campaign. The cancellation attempt was one of the most determined we’ve ever seen in Finland. Fortunately, Louhimies had enough clout and international connections to salvage his career.

Defeat

It is important to keep in mind the distinction between the Winter War and the Continuation War. Around the world, the Winter War is understood as a simplistic good vs. evil struggle, a David vs. Goliath narrative that is easy to market and easy for a nation to feel proud about. In an earlier piece I’ve talked about how that narrative is at least partly false. Here I’m only interested in how matters are generally perceived, not in how they actually are.

The narrative around the Continuation War is much more complicated. Finland was essentially an Axis country fighting side by side with the Germans against the Allies, albeit only on the Eastern Front. In addition, the defeat we suffered is less easy to sugar coat than with the Winter War. In Finland it’s been a traditional coping method to perceive the Continuation War as a wholly separate war, as a literal continuation of the Winter War. As a war that had nothing to do with Barbarossa or the general Axis war effort. I don’t think most people who make use of it really believe it themselves.

The movie certainly doesn’t. In the film Finns are clearly presented as allies of Germany, with Finnish and Swastika flags flying side by side, with German troops shown marching in Finland, Finnish officers toasting to the might of Germany, etc. No cope, no obfuscation.

Neither is there cope or obfuscation in how the film handles our defeat. You really get to taste its bitterness through the screen. The defeat feels like a long churn. The men know it’s coming. They’ve suspected since Stalingrad, they’ve known since D-Day. But they are forced to fight on, in a state of demoralization. Among the rank and file many are able to adopt the superficial view that at least defeat will mean an end to the day to day hardship on the front, and gain some relief out of the notion. But with the officers who have a keener understanding, there’s really no consolation.

One key scene omitted from the film versions comes at the very end of the novel. Second lieutenant Jalovaara sits separate from the others in the middle of the forest, letting the news of defeat sink in. Thus far he has been able to hope against hope, deny the inevitable and keep on going. No longer. He lets his head sink to his hands, staring at the ground without moving.

Then his eyes begin to fill with tears. For a long time he bites his teeth trying to steel himself. But then the shoulders begin to tremble, and the bitter, violent weeping of a grown man begins to shake him. Amid the sobbing, and between the still gritted teeth, he keeps on repeating: “We heard… We were told… Finland is dead… Its graves covered by snow… By snow…”

The deeper minds in Finland understood immediately that what had happened was not only a defeat for us Finns, but a defeat for Old Europe, a defeat for a way of life, for a whole Weltanschauung.

The end result of the war and all its consequences help explain why the film tends to feel so surreal. It’s because the film presents the modern audience with a reactionary world, all while using modern actors and modern film technology.

It offers us a startling glimpse behind a granite wall, into what once was. A vision of long since defeated normalcy, piety, propriety, confidence, and identity. It makes us admit that their loss was in the end of greater consequence than the material defeat the film depicts. It is the sight of old virtues that so attracts us to this story of a lost war.