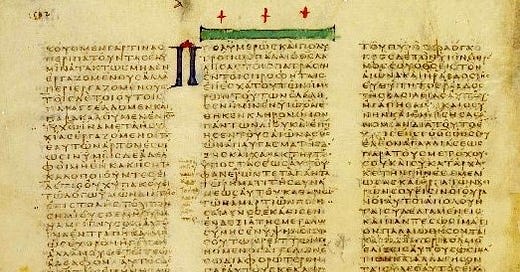

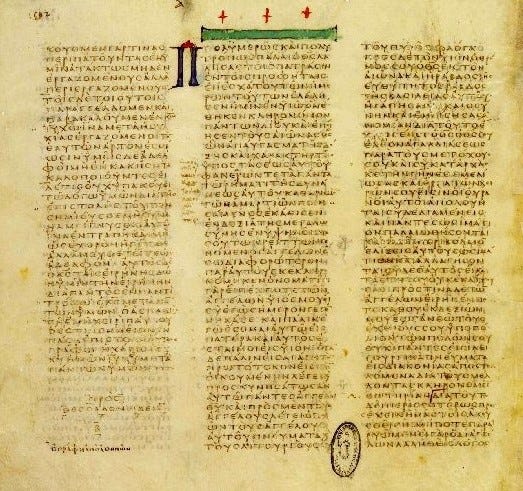

The consequence of Alexander’s conquest was the cultural hegemony of Hellenism. Representing one of the great Hellenistic achievements, the great library of Alexandria strove to include all the books of the world in its collection. But a key work was missing: the Bible of the Jews. We are told how the king of Egypt, Ptolemy II Philadelphus ordered the grand work of translation around 270 BC. Seventy-two (or 70, according to Josephus) learned scribes were invited from from Judea and got to work. The result was the Greek Bible – a new Revelation which was to change the world.

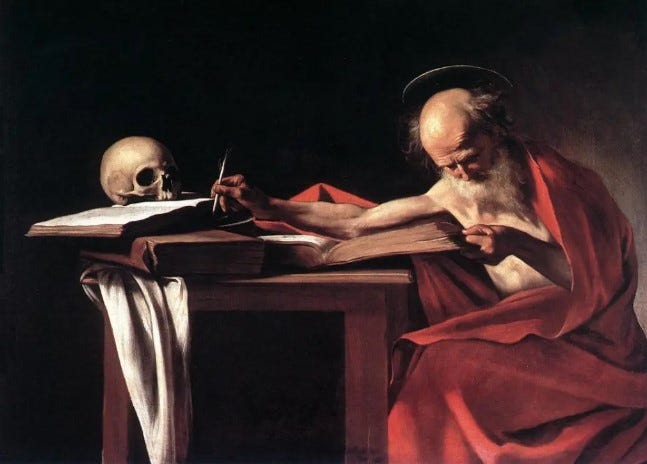

Named after the seventy sages who accomplished the project, the Septuagint is now widely ignored by Christians, whereas there is a peculiar fascination with the Hebrew Bible. Often the fascination is perceived to be a particularly Protestant phenomenon, but the irony is that the Protestants have adopted their position from St. Jerome, the creator of the Latin Vulgate. It tends to come as a shocking realization that the Vulgate itself is mostly based on the Hebrew Bible. In fact, the Vulgate represented a revolt against Church tradition which had always been based on the Septuagint, the Greek Bible used by the Apostles, and quoted by our Lord himself.

True origins

As Timothy Law points out in his excellent book When God Spoke Greek (2013), the adoration of the Hebrew Bible is usually based on the idea that it is “the original”. But the fact is that the Masoretic Text (the technical name for the Hebrew Bible) was only finalized in Medieval times, whereas the Septuagint was mostly written in the third century BC, with some of the minor books following in the second and first centuries BC. Jews and others may claim that the Hebrew Bible has been kept unchanged throughout the centuries by careful scribes, but the claim is unfounded.

The Dead Sea scrolls reveal to us that the Masoretic Text is only one of many textual variants that existed in ancient times. What’s remarkable is that when Dead Sea manuscripts are studied, we find that in many cases the Septuagint reflects more ancient textual forms than does the Masoretic! It certainly isn’t a clear cut case – in some cases the Masoretic may represent an older textual form, but in others the Septuagint is more ancient.

The idea that the Hebrew Bible as we know it is the “original” is wrong in several ways. Firstly, we can indeed prove that in many cases the Septuagint represents older textual forms. And secondly, the multiplicity of textual forms extant in ancient times shows that it’s impossible to pick any truly “original” text. There were several variants in use simultaneously.

It is probable that the Masoretic Text ended up becoming authoritative quite arbitrarily. Out of all possible alternative textual versions it just happened to be the one that remained in the Jews’ easy disposal after the destruction of the Temple, when rabbinic Judaism as we know it first began to form, having to place added focus on the scripture and scriptural authority.

What’s more, the Septuagint had been translated and established long before (over a 1000 years before!) the Hebrew Bible finally became solidified in the form which is now used in most modern Christian Bible translations. In truth, the Septuagint was the first time in history that the Old Testament reached a more or less stable form. According to church fathers, this was the special work of the Lord. An important way in which God prepared the world for Christ and his church. Once he had spoken in Hebrew to the Jews. Now he had spoken in Greek for the church of Christ.

“The prophecies of our Lord were concealed in the Hebrew language of the Jewish scriptures, but God providentially guided a translation into Greek so that when the Savior of the world would appear the nations would recognize him.”

- Eusebius

The idea is that because God foreknew the Jews would end up betraying their redeemer, he put aside his original revelation he had made in Hebrew, and prepared the way for the Good News by speaking anew in Greek.

Mismatch

Another crucial problem is that the Hebrew Bible is fundamentally alien to Christianity. First of all, the Bible the Apostles and the New Testament authors used was the Septuagint. That’s the Bible they quote back to 80-90% of the time. This includes Jesus himself. When he quotes Isaiah, the sense and word form is the Septuagint Isaiah, not the Hebrew Bible Isaiah.

This is not just a matter of flair, but a matter of theology, sometimes theology that cuts very deep. It is only the Septuagint Isaiah that prophecies of the virgin birth. That’s the Isaiah that Matthew quotes when he says the prophecy had been fulfilled in Jesus.

'The virgin will conceive and give birth to a son, and they will call him Immanuel'

The crucial point is that this prophecy is only found in the Septuagint. The Hebrew version of Isaiah only prophesies that a young woman shall conceive. Thus, only the Septuagint offers us one of the key prophecies fulfilled in Jesus.

Many ancient Christians learned about these discrepancies, but were not disturbed by them. St. Augustine and others argued that differences are only to be expected, because we know the Septuagint is the Bible of the Church, and that it had been divinely inspired by the Spirit of God. The translation itself is miraculous, and part of the process of gradual revelation God has deemed wise.

Thus, the Septuagint was not just a translation, but a new, fuller Revelation. What some perceive to be simple errors in translation are in fact the Spirit of the Lord at work. Human error can fulfill a divine purpose. It is illustrative of this trust that most of the church fathers showed absolutely no concern or interest in discovering how accurately the Greek Septuagint represented the Hebrew Bible.

We must also note the obvious fact that the New Testament itself is written in Greek, and as such forms a stylistic and linguistic whole with the Septuagint, not with the Hebrew Bible. St Paul wrote his letters against the backdrop of the Septuagint. St John had a particularly Greek, Logos-centric, philosophical mindset in his Gospel. The tonal atmosphere and philosophical core of Christianity are deeply Hellenistic, and this reality fits like a glove with the Septuagint.

“A single hour lovingly devoted to the text of the Septuagint will further our exegetical knowledge of the Pauline epistles more than a whole day spent over a commentary.”

- Adolf Deissmann

When you then proceed to replace the Septuagint with the Hebrew Bible, you create a disturbing mismatch. What used to be wholly Greek is now broken at the middle. The tone longer fits. The quotations no longer match. The language is all wrong. The Testaments become disjointed, needless distance is placed between the Old and the New. Their ability to speak to each other is hindered.

Abandoning the Septuagint and adopting the Hebrew Bible also creates unnecessary trouble with the so called Apocryphal or Deuterocanonical books of the Old Testament. They are all included in the Septuagint, but none of them are included in the Hebrew Bible. If you follow early church tradition and the Greek Bible, you will keep hold of them. If you abandon the early church tradition and follow the Jews, you will ditch them – or at least cordon them off.

Jerome’s folly

We know that the Septuagint is something like 1200 years older than the Masoretic Text used in most Bible translations. We know that the idea that the Masoretic text is “the original” is false and wrongheaded. And we know that it was the Septuagint that the Apostles used and it is the Septuagint that the New Testament meshes with stylistically, linguistically, as well as in terms of teaching and quotation.

In fact, the concepts Old and New Testament are themselves drawn from the Septuagint. Same is true with such Christian terminology as the Lord (kyrios, replacing the YHWH of the Hebrew Bible) and Christ (Christos, the Greek translation of messiah). It is clear this is no small matter we are discussing.

Given all this weight behind the Septuagint, why the change? Partly it was due to a mistake. The shift towards Hebrew was driven by St Jerome, who mistakenly believed that the New Testament authors had used the Hebrew Bible, which was one of his key justifications for abandoning the Septuagint. St Augustine and others knew better, and tried to argue him out of his foolish project. Alas, Jerome was nothing if not stubborn.

Another motive of his was that he had to frequently interact with Jews, and desired to convert them and to argue against them. To do so he needed to know their Bible well so as to argue convincingly. But of course going from this limited practical purpose to the wholesale replacement of the Septuagint seems quite baseless.

Another reason was that before Jerome’s time Origen had already made an influential new edition of the Septuagint which included a heavy influence from the Hebrew Bible in the form of a kind of critical apparatus. Later on this critical apparatus was often placed inside the text itself, causing a kind of adulteration. Jerome could now argue that most Greek Bibles had already been ‘hebraized’ to some degree, so why not go the whole hog?

The disagreement between Jerome and Augustine continued throughout the decades. Part of it was due to their different understanding regarding the philosophy of language. For Jerome truth was connected to the Hebrew language itself. Sign was greater than the thing signified. This same way of thinking ended up influencing Reformation thinkers.

Augustine, on the other hand, regarded language in the opposite way. For him language was only a marker of the real thing behind it. The thing signified was superior to the sign. God was real, and language only pointed at him. He pointed out that supreme clarity in language was not necessarily a wise desire either, because it may be part of God’s wisdom and goodness to obfuscate the signs so that we may not become too prideful in our understanding of scripture.

Another argument Augustine used against Jerome was asking if he wasn’t riddled with hubris. After all, if the 72 translators had not been able to grasp the obscurities in Hebrew which Jerome now sought to correct, what made him (with his lately and haphazardly acquired Hebrew skills) so confident that he could reach a superior outcome?

“We are right in believing that the translators of the Septuagint had received the spirit of prophecy; and so if, with its authority, they altered anything and used expressions in their translation different from those of the original, we should not doubt that these expressions also were divinely inspired.”

– St Augustine

Regardless of whether Jerome could succeed or not, there remained great wisdom in keeping hold of the universality of Greek. After all, Hebrew is a locked down, fossilized, tribal language: practically nobody knows it. Who then can challenge Jerome and the accuracy his translation? In practice he becomes the lone guardian of truth. With a translation from Greek this is not so, as Greek is a universal language and most well educated people could always check and challenge any and all claims.

Furthermore, Augustine warned that given that there was no way the Greek speaking East would ever give up the Septuagint, if the Latin West decided to go against the Greek tradition in its translations, it would risk splitting the Church in half.

Nevertheless, why did Jerome’s Vulgate become so prevalent given all the high level opposition and given all that was good about the Septuagint? Mainly it was about a desire for stability. The older Latin translations were splintered and fragmented. There was a great practical need for anything that could help unify the Western Church amid the cataclysmic situation of fifth century Rome. Jerome’s Vulgate was really the only thing that fit the bill, despite all the issues behind his Old Testament translation.

It must also be remarked, that Jerome had done a great job in terms of polish, clarity and linguistic quality. His Vulgate was a huge technical improvement over the old Latin translations that had existed earlier. Its rise wasn’t an immediate change, however, more a process that lasted centuries, culminating only in the definitive endorsement in the Council of Trent in 1546. Be that as it may, with Jerome’s accomplishment began the gradual decline of the Septuagint in the Western Church.

Supreme irony

We have seen how the hebraization process of the Old Testament had deep roots in the Church, so there was really nothing new about Martin Luther’s love for the Masoretic Text. It is remarkably ironic, however, that Luther and the other reformers picked the Hebrew Bible as a target of adoration. Not only was the scorned Latin Vulgate already based on it – the early church that they idolized had never used it!

It is estimated that something like 25% of Jerome’s Vulgate was still based on the Septuagint, and something like 75% was translated from Hebrew. In effect, it was this remaining quarter of the Greek influence that the Reformers wanted to make sure was removed from their Bibles. In so doing they eradicated what was left of the Bible used by the early church.

Protestant Bible scholars and students often hope that by studying the Hebrew Bible they can reach a closer understanding of the original word of God. The stinging irony is that in fact the Hebrew Bible contains a lot of very late material added long after the Septuagint already existed in a stable form.

All the ironies involved are probably beyond counting, but I shall here compile a list of some of the more egregious ones:

The Reformers chose the less Gospel-attuned Bible, where a young woman conceives instead of a virgin.

The Reformers chose the Bible that wasn’t normally used by the New Testament authors nor quoted by our Lord.

The Reformers chose the Bible wholly alien to the early church.

The Reformers chose the Bible that had been defined, authorized and upheld by the post-Temple Jewish community, who actively rejected Christ and opposed Christianity.

The Reformers chose the Bible that commits them to a Jewish canon foreign to the early church, to whom the so called apocryphal books were just as valid as all the others. A further irony is that the Catholics, who retained those books within the canon, remained closer to the early Christians.

The Reformers chose the Bible that is radically more difficult for the average person to learn to read than the Greek Bible they shirked. This of course goes straight against one of their core principles: the wide accessibility of the Bible.

The Reformers chose the Bible that mutes or eliminates many of the messianic prophesies and theological messages important to Christianity. This is particularly problematic if your principle is ‘scripture alone’.

The Reformers chose the Bible that is most dependent on trust in tradition, in this case the Masoretic tradition of Jewish scribes.

The Reformers chose the Bible that causes the Old and New Testaments to needlessly clash, creating unnecessary complications. This is ironic for a movement which claimed to strive for simplicity.

The Reformers chose the Bible that was not translated, believing it more credible than a translation could be. This is ironic for a movement that strongly advocated Bible translation.

The Reformers chose the Bible that puts them in opposition with St Augustine, their usual hero.

The Reformers chose the Bible that was used in the Latin Vulgate which they sought to oppose.

With Catholics having to a large part fallen in the same Masoretic trap, it’s only the Greek Orthodox who remain well in touch with the Septuagint.

Looking back at this story, we cannot but admit that the contradictions caused by following the Hebrew Bible appear insurmountable. The Septuagint of the Apostles must be reclaimed, the Testaments unified, Hebrew-worship debunked, and anti-Hellenic attitudes revealed. Thus only may the fracture within scripture be mended.

I enjoyed reading this.

There are some proof errors.

Did you know that Martin Luther was not a Hebrew scholar and translated almost exclusively from the Septuagint? It is the reason modern German syntax mirrors Greek, rather than Hebrew.