Typical readings of the French Revolution are split neatly in two camps, with secular republicans on one side, and Christian monarchist on the other. However, sometimes the split isn’t quite so neat. Hilaire Belloc’s views on the matter – illustrated in his book The French Revolution (1911) – constitute one such example. The man was a devout Catholic but also an zealous Republican.

A somewhat less glaring but still peculiar mixture of ideas is offered by Alexis de Tocqueville in his The Ancien Regime and the Revolution (1856). In Tocqueville’s thinking are combined a love for liberalism and a dislike of equality; a progressive political ethos matched with a romantic temperament.

Democratic Catholicism?

Belloc’s outline of the Revolution begins with an explanation of its political theory based on Rousseau. Belloc deeply admires Rousseau and believes his seminal work The Social Contract impossible to refute. This is strange, because in a previous article I showed how Rousseau’s book is filled with peculiar cynicism and venomous anti-Christianity. Belloc is willing to excuse all the anti-Christianity as Rousseau simply being ‘a man of his times.’ This is the same argument he uses with all of the revolutionaries.

“Rousseau’s pages are the direct source of the theory of the modern State; their lucidity and unmatched economy of diction; their rigid analysis, their epigrammatic judgment and wisdom – these are the reservoirs from whence modern democracy has flowed. What are now proved to be the errors of democracy are errors against which the Contrat Social warned men. The moral apology of democracy is the moral apology written by Rousseau.

If in this one point of religion he struck a more confused and a less determined note than in the rest, it must be remembered that in his time no other man understood what part religion played in human affairs.”

Starting with Rousseau, Belloc’s outline ends with the death of Robespierre (in 1794), for whom Belloc acts as an apologist, as you may have guessed. According to Belloc, Robespierre did not lead the Terror, but secretly opposed it.

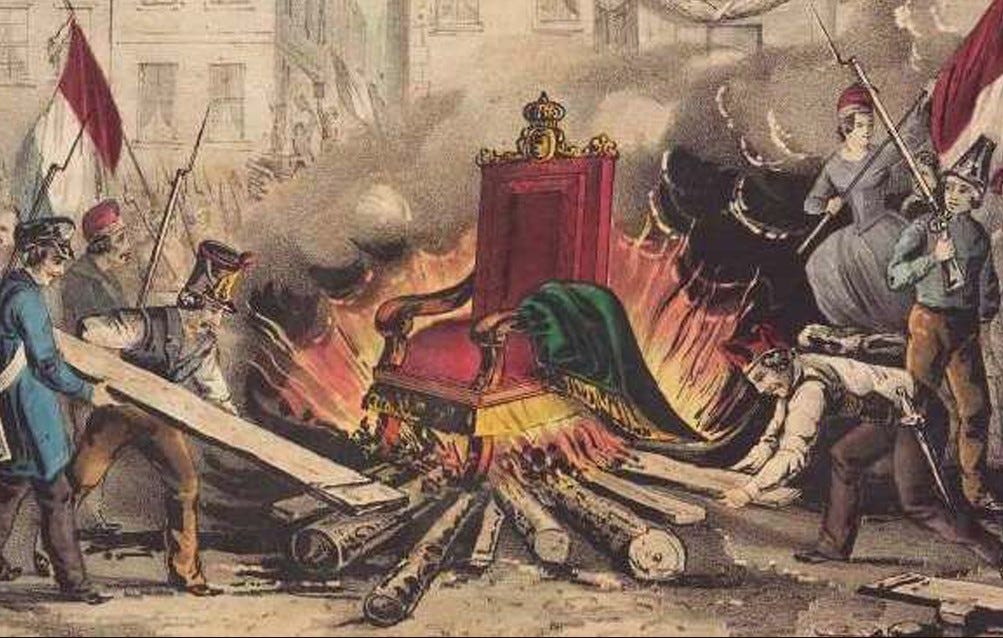

The book goes through the major historical events politically, socially, and militarily. The short work is very effective at offering a clear and colorful picture of a messy period. But the pro-revolutionary interpretation is laid very thick. Throughout reading it I felt puzzled and sometimes bewildered. For example, what can drive a devout Catholic to minimize the Terror, explaining it away as simple martial law, necessitated by external invasion?

Similarly, to this day I cannot quite fathom why Belloc tries to minimize the religious destruction caused by the Revolution, and to maintain that there was no necessary conflict between the Church and the Revolution – everything being only a big misunderstanding, for which the Church was in a large part to blame.

An example of Belloc’s pro-revolutionary approach can be found in the descriptions he offers of all the key players. Generally, the pro-monarchy forces from the King and Queen downwards are drawn in muted colors, as fairly unsympathetic and unimpressive people. While in some degree this may be true to life, and even offering one explanation for the success of the Revolution, the situation becomes glaring when one reads Belloc’s accounts of the radical revolutionary figures.

Here are two examples from extreme ends:

King Louis XVI:

“He was very slow of thought, and very slow of decision. His physical movements were slow. The movement of his eyes was notably slow. He had a way of falling asleep under the effort of fatigue at the most incongruous moments. The things that amused him were of the largest and most superficial kind…. He was possessed of all the elements of the Catholic faith.”

Even the latter off-hand admission does not soften the overall treatment Belloc gives the King. It is strange, by the way, how Belloc can argue that the times were such that nobody of note in France understood or upheld the faith, when he admits the King himself did!

Marat:

“Marat is easily judged. The complete sincerity of the enthusiast is not difficult to appreciate when his enthusiasm is devoted to a simple human ideal which has been, as it were, fundamental and common to the human race. Equality within the State and the government of the State by its general will: these primal dogmas, on the reversion to which the whole Revolution turned, were Marat’s creed.

Those who would ridicule or condemn him because he held such a creed, are manifestly incapable of discussing the matter at all. The ridicule and the condemnation under which Marat justly falls do not attach to the patent moral truths he held, but to the manner in which he held them.”

Consider how a Catholic king on the on hand and a revolutionary butcher on the other are described in such a tone and tenor, by a devoutly Catholic author. You needn’t imagine my puzzlement.

The only way out of the labyrinth is to take the petty path of kitchen psychology. I can only guess that Belloc was such a vehement French patriot he could not but defend the Revolution, as the whole of French patriotism is built on pro-Revolutionary ethos. In his mind denying the revolution would have been to deny France. Combine this with vague whiggish views he had absorbed growing up in late Victorian England, and we have something like an explanation in our hands.

Religious war

Tocqueville’s approach feels much more balanced, albeit sometimes coming close to fence sitting. By temperament he was of the romantic type, a supporter of liberalism but against equality, though he perceives the latter as practically inevitable. He hates centralization and has nostalgia and sympathy for the old nobility and for the Church. At the same time he recognizes that France was in an impasse. Something had to give.

Tocqueville’s main thesis is to argue that in many regards the Revolution wasn’t so much a refutation of the Ancien Regime, as its fulfillment. This is true especially in terms of the centralization of society, which was a project begun by absolutist monarchy, and completed by the Revolution.

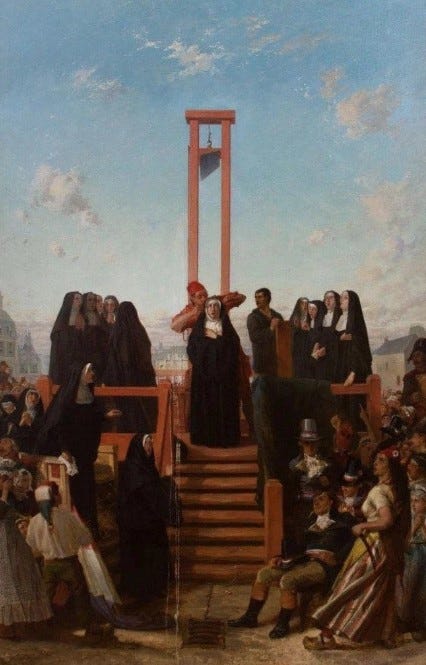

He points out that the ultimate driving force of the revolutionary ideology was not liberalism but anti-Christianity. Even after Napoleon had largely quenched the liberal dreams, the revolutionaries stuck to their gains and maintained that the destruction caused to the Church was a sweet enough victory.

Tocqueville characterizes the Revolution as not only a political revolution, but fundamentally a religious war, in many ways like the Thirty-years war, or like the Islamic conquests. This is to say that normally a revolution is either political or religious. But in all three instances it was both at the same time.

Ironically, Christianity in fact strengthened for some decades after the Revolution. This is in part because before the Revolution the Church had been a deeply ingrained political force, which had stifled its spirit, cluttered its purely religious operation, and made it an easy target for revolutionary hatred.

Fundamentally Tocqueville is in agreement with Belloc’s view that there needn’t have been any conflict or contradiction between the Church and the Revolution. It was all some tragic accident. Both men believe that democratic political theory and the Catholic faith are in fundamental harmony with each other. However, neither of them offers an explanation of how to combine a distinctly monarchical and hierarchical religion with a democratic, anti-hierarchical political theory. To return for a moment to kitchen psychology, both men are wanting to have the cake and eat it, despite all the cognitive dissonance.

Abolition of aristocracy

Social leveling was another way in which the Ancien Regime and the Revolution matched each other. Royal absolutism had already largely stripped society from its old feudal hierarchies, removing power divisions and demolishing rival castles by giving everything to the King. Replacing the King by the Committee of Public Safety changes the forms, but keeps the dynamics of power intact.

The lasting change effected by the Revolution was the absolute destruction feudalism and all its remnants, not only from France but from all of Europe. Europe had been built on a feudal heritage, and as such the old system was involved in everything. This also meant that its obliteration affected everything, which made the Revolution feel so total and all-encompassing. However, like a true progressive, Tocqueville argues that this shift to an equalized, anti-feudal society would have happened anyway, inevitably, but through gradual steps instead of a chaotic upheaval.

Paradoxically, and reminding us of the Russian Revolution, the French Revolution happened in the place in Europe where the weight of old feudalism was least burdensome. The place where peasants were freest and the aristocracy politically weakest. The old feudal structures were much more firmly in place in Germany, for example, but without any revolutionary fervor. Even within France, it was the people in the liberal, prosperous, distinctly non-feudal cities which were most enthused by revolutionary ideas. The provincial folk whose lives were still affected by feudalism actually revolted against the Revolution, and had to be destroyed by Paris.

To explain this, Tocqueville notes it is in fact the weakening of feudalism that makes the system feel more intolerable. The nobility needs to be politically powerful for its privileges to appear palatable to the people. A dependent nobility that is only able to exist under the auspices of the King, loses its legitimacy. In order to function and remain accepted, feudalism cannot be merely civil or formal, it must to be political.

Tocqueville uses England as a point of contrast. England was the only country in Europe where aristocracy grew more powerful, not less. This was achieved by making it less like a caste. That’s to say that new money had access to the aristocracy, and that the definition of an aristocrat was made more hazy. The delineation between aristocrats and non-aristocrats wasn’t so clear in England. This was the reverse of France, where the matter was always absolute and obvious. Either you belonged in the caste or you didn’t. You could enter if you could afford the privilege, but only through a royal warrant. After that moment your social and legal status changed in an immediate and absolute fashion.

But at the same time there was something disgustingly fake about it all. The French aristocrats had great privilege and a great sense of exclusivity, but no real power. On the other hand, in England the aristocrats made concessions regarding their privileges and with the sense of exclusivity, but in so doing greatly increased and stabilized their hold on politics.

In England all sense of caste was thoroughly replaced by the more vague notion of class. It is ironic in a way that the most hierarchically class based society in Europe was also the most strictly anti-caste society in the world.

Though Tocqueville has little sympathy for the degraded aristocracy, he is a romantic at heart and mourns the loss of the nobility. In his view the nobles gave a manly example to the whole nation, and even their bitterest enemies become weaker and meaner without the nobles’ uplifting influence.

Secularism unleashed

The French had been a remarkably free people before the Revolution. Characteristic of Ancien Regime was that its laws were strict but their execution lax. All laws had their exceptions and there was much leeway. Many problems could be solved with money and with quick thinking. The law was never uniform and equal, nor was that the goal. The law depended on your class and always came with case by case exceptions. Overall the nation was free, but the nature of its freedom was spasmodic and irregular. Yet in many ways concerning everyday life, men had been more free before the Revolution, and its centralizing, standardizing and systematizing fervor.

Another consequence of royal absolutism was that French society didn’t really have any sense of politics. There were no parties, there were no political structures at the level of the wider nation. This meant that the writers and philosophers became like party leaders. From there the Revolution gained its idealized, religious spirit. It wasn’t directed by concrete politics but by philosophical abstractions.

The royal efforts to curb this development were lacking. As Tocqueville puts it, the radical authors and philosophers were persecuted only so much as to make them complain. The King should have realized that even a complete freedom of press is less damaging than partial, halfhearted censorship. Another point of contrast with England is that the English intellectuals and opinion formers rejected anti-religious views autonomously. In England their suppression and rejection required no governmental or centrally led action.

The radical thinkers created a unique situation in 18th century France. Alone in the world it became a place where irreligion became both wide spread and passionate. Tocqueville laments how this created a very dangerous state in the souls of men. In the case of the lower classes it bred dangerous, brutish cynicism, and in the case of the upper classes a dangerous, zealous idealism. In this respect the French Revolution was a reverse of the Reformation. In the Reformation it was the commoners who were idealistic and sincerely enthused by Luther and company, whereas the nobility were the cynical ones only using Protestantism as a tool for power games.

Tocqueville argues that the causes for this sea change in religious views were social and political, not religious. Unlike Belloc, he praises the French clergy for their faithfulness, arguing that the French Church was considerably less corrupt than others. He argues that it was simply the case that in practical terms the revolutionary thinkers felt they had to attack the Church and destroy its hold. Firstly because the Church was to a large part in charge of the censorship directed against radical thinkers, and more fundamentally because the Church functioned as the guide and ‘control mechanism’ for the minds and hearts of men.

The weakening of religion, first in the intelligentsia and then among the commoners, led to the unleashing of the the nation from the guidance of the Church. The radical consequences were felt immediately, and continue to be felt today. In the end, the greatest result of the Revolution wasn’t the spread of democracy and republican values. Those were in fact largely quenched in the 19th century, and again in the first half of the 20th, only to properly re-emerge after the Cold War.

The real fruit of the Revolution was the spread and intensification of secularism throughout the world. Secularism, not democracy, is the paradigm that has most consistently characterized and enervated Modernity ever since.