Arnold J. Toynbee’s masterpiece in meta-history (A Study of History, 1934-1961) includes a deep analysis of the different approaches a society can adopt when suffering existential exhaustion. The analysis reaches a special poignancy because of its applicability to the life of an individual. The spiritual wound is not only observable in the society as a whole, but finds its parallel within the souls of each of its sensitive members. The four paths Toynbee outlines are archaism, futurism, detachment and transfiguration.

Archaism

When a society begins to reach a point of desperation, the sensitive minority will quickly realize that something has to give, things can’t go on like this. The first reaction is reaction. That is to say, nostalgic hankering for turning back the clock back to the good old days.

The most famous historical examples include the Roman senatorial class of the late republic, especially figures like the Gracchi brothers and Cato the Younger, culminating with the desperate actions of Brutus and his co-conspirators.

Dead institutions like the tribunate of the plebs were artificially resurrected and bolted onto a society that had already transformed – ravaged by Hannibal and the Punic Wars, its strong backbone of free peasantry broken, plagued instead by a wanton city proletariat, and saddled with manifold imperial possessions and responsibilities.

The adoration and resurrection of ancient institutions wouldn’t work, because they no longer matched with the society as it had become. At their best, these archaisms can only work as painkillers and charades. A good example is the way how Augustus and his successors used the appearances republican institutions to establish a sense of superficial stability and continuum, to obfuscate the drastic break in form of government from oligarchy to monarchy. To offer a reverse example, in Britain the Crown was allowed to retain its outer trappings, and old institutions were superficially venerated, although in fact the system had changed from a monarchy to an oligarchy.

Where archaism doesn’t utterly fail, it’s still surrounded by a sense of futility and artificiality. It can only amount to a lubrication or an opiate that helps lull the more conservative elements of society. The attempt is always incoherent, because the past and the present can never be reconciled. You cannot twice step into the same flowing waters. If the archaist attempts to rebuild the past in the present, the unavoidable movement of the times will shatter his brittle construction. If, in turn, he sets his focus on the here and now, and understands archaisms only as tools for coping with the inevitable present, they become fake and deceptive – only an opiate.

Paradoxically, archaism tends to only feed the flames of futurism, by either making the resurrected institutions shatter, proving their weakness, or by erecting something that is fake and inauthentic, which all thinking men will find distasteful. The reaction that ensues from the archaist’s failure is either a desperate jump into a supposed future, or a philosophical detachment from the world.

Detachment

After pursuing a career as an archaist, Cato the Younger met his end in a great climax of detachment. It was in this moment of complete surrender and suicide that he first became a threat to Caesar. Archaists had been trivial opponents to the great man of history. But someone who could detach himself was in a real sense beyond Caesar’s reach.

It tells us much of Caesar’s wisdom that he immediately realized the gravity of what had happened, and reacted by writing against Cato – attacking his memory and example with words and rhetoric, taking the form of his pamphlet ‘Anticato’. Cato was now beyond worldly power, and rhetoric was the only choice.

Regardless of these attempts, Cato’s example lived on and inspired many into anti-monarchist activity that ultimately ended Caesar’s life.

While sometimes powerful in the example it sets, the problem with this path is that it isn’t at all incidental that Cato’s life ended in suicide. Suicide is built into philosophies that set detachment as their goal. This is true both in Asian though influenced by Buddhism (did you ever wonder why Japanese stories are riddled with suicide?) and with Western thought influenced by Stoicism. Both of them involve a condemnation of life, and of the best things in life.

Indeed, to be a consistent Stoic you must become a monster.

Epictetus advises his readers:

“If you are kissing a child of yours… never put your imagination unreservedly into the act and never give your emotion free rein…. Indeed, there is no harm in accompanying the act of kissing the child with whispering over him, ‘Tomorrow you will die.’”

And Seneca adds:

“Pity is a madness induced by the spectacle of other people’s miseries. The sage does not succumb to such mental illness.”

Seneca and Epictetus are nothing if not logical thinkers. It is true that if you accept the Stoic axiom of “life unperturbed” you must eradicate love. Everyone of us knows that love is the surest way to destabilize our lives, to drive our emotions into uproar, and to risk heartbreak and foolish decisions. The trouble is that detachment like this is anti-human. It either spiritually truncates or quite literally kills the one whom it is supposedly trying to help.

As Toynbee puts it:

“In consulting only the head and ignoring the heart it is arbitrarily putting asunder what God has joined together. This philosophy of detachment has to be eclipsed by the mystery of transfiguration.”

To this transfiguration we shall return after discussing futurism.

Futurism

Like his fellow time-traveler the archaist, a futurist is likewise saddled, angered, and frustrated by the problems of the present moment. Instead of trying to return to the past, he attempts to summon in the future. The peculiar weakness of futurism is its opposition to human nature. What a troubled man naturally wishes for is to return to his safe, nostalgic childhood. To the average psyche, even a disagreeable present is preferable to an unknown future. As was pointed out, normally the path of futurism is only taken after the path of archaism has already been attempted, and failure has ensued – the brittle archaistic construct has shattered, or it has been revealed as something inauthentic.

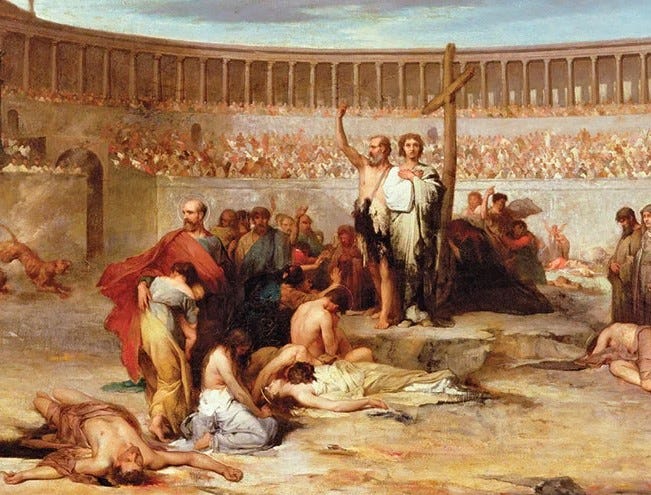

The frustrated observer thinks: “If turning the clock back wasn’t the answer, why not try turning it forward?” Unfortunately this attempt involves many of the same incoherencies, as well as special problems of its own. Famous examples of futurism include the reforms of Peter the Great in Russia and of the Meiji period in Japan. Futurism was also the approach involved in the Jewish messianic rebellions against Rome – misguided attempts at pushing a dreamed of future state into a worldly reality.

Perhaps the most illustrative examples of such ambition and impatience are the great revolutions, both the French and the Russian. They reveal how futurism has an inherent tendency towards the totalitarian. The relics of the past and of the present must be annihilated to make way for a new system. Whole ways of life must be put to an end, and sometimes whole classes of people must be liquidated (such as the nobility, royalty, clergy, the land owners, etc.).

While futurism may at times lead to some political success if applied with halfhearted pragmatism instead of wholehearted idealism, its internal effect is again a sense of disillusionment. The present always remains, and even the political achievements will taste like ash, because man does not live by bread alone. But perhaps this disillusionment can lead to a positive change that allows futurism to transcend itself?

Transfiguration

By studying history we come to understand that the path of transfiguration uniquely reached after the Jewish futurism centered around the worldly Kingdom of Judah was shown to be a dead end. Through perfect disillusionment with their worldly dream, the Apostles of Christ came to find the Kingdom of God.

In the mean time the stiff necked futurists kept on banging their heads against the might of Rome until they were utterly destroyed. Those few who took the path of Transfiguration rose above Rome and ultimately made her their own. The power that had defeated them materially was conquered by them spiritually.

What’s notable is that it was not just about some simple call for divine assistance. The Jewish futurists had always believed God was on their side, which had made their repeated failure all the more puzzling. What separates transfiguration from futurism is letting go of your own plans, and beginning instead to pursue God’s plans. God had something infinitely mightier in mind than the construction of one more earthly kingdom among many.

The power behind the Christian mindset was not just the age-old idea “God is with us”, but the psychologically revolutionary attitude of “God wills it.” Because the Christians’ newfound purpose was not Man’s, but of God’s, it could only be pursued spiritually. God was no longer understood as a strong ally in some earthly endeavor, but as the great generalissimo whom you must obey and whose divine plan of action you must partake in.

Through transfiguration we can stop believing in dreams about the imagined future of this world, and replace them with a true revelation of the world beyond. The downfall of worldly hopes opens us up to a higher reality. This has been the experience of Western Civilization as well as the common fate of the individuals who constitute it.

The other option before the disillusioned disciples would have been to detach like the Stoics or the Essenes of the desert. And it is true that a sense of detachment was involved here as well. Jesus himself did detach himself into the wilderness to be tempted. After encountering Christ on the Damascene road, St Paul spent three years in Arabia, detached from the present. A sense of detachment has always been a part of the life of a Christian, most obviously with the monastics, but also for Christians who live in the world at large. After all, there are many worldly things you must keep yourself detached from.

What separates transfiguration from detachment is that the transfigured one returns to the world. Like Christ after his desert seclusion, or after the three days in the tomb. Or, taking the wider view, as the Son of God inserted himself to his creation through the Incarnation. Indeed, this is the greatest stumbling block the ancient philosopher encounters in Christianity.

The philosopher would find the divine existence perfect – perfectly detached from the troubles of the world, the ultimate nirvana. Why would God want to give all that away and deliberately involve himself with the troubles of life in a broken world, and with the pains and passions of mortality? Why “regress” like that?

The shocking answer to this philosophic puzzle resounds throughout Western culture:

“God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten son.”

There it is. The Good News founded on love. The solution to our dilemmas is the very thing that the detached philosophers are keenest to avoid. Inner tranquility can never cope with the wild power that is love. The path to nirvana must be immediately abandoned by anyone who desires to fall in love or to feel pity for the victims of injustice.

We are not omnipotent, we are not omniscient, we are not omnipresent. We are nothing omni. We are limited, we are weak, we are foolish. What then can connect imperfect Man to his perfect Creator? The golden thread of love. Both the love we will and feel towards others, and the divine love that saves us. This is the key divine quality we partake in, one that can save both us and our society from desperation and death.

The great philosophic irony is that love is the very stone abandoned by the builders in their supposed wisdom. The abandoned stone became the cornerstone of the new world built by those who took the path of transfiguration.

I will always share the refrain from C.S. Lewis, The Screwtape Letters; "Keep your patient focused on anything but two moments: his immediate present, and his eternal future. In the latter he will find the Enemy; in the former, he will find his path the to Enemy."

Paraphrasing, but that's the gist of the tale. Thank you Finrod!

eh, here I started to thinking the essay was developing into something interesting and then it culminates in handwavy exclamations that will ring hollow to everyone other than Christians