Love is the source and summit of life, but it is also maddening, destructive and dangerous. “The traitor of the heart and soul.” This eternal contradiction is explored by Ariosto in his masterpiece of chivalric Romance, Orlando Furioso (1532). The poet worked at his epic for 27 years, and the result is by turns intensely cynical and charmingly sentimental.

Ariosto will show us how wives betray their husbands, and how husbands are false to their wives. He’ll show how sweet and pure women can be, and how heroic and admirable is manhood at its best. Ariosto combines the emotional drama with an wild cavalcade of high-adventure and with his boyish sense of humor.

Much of the following analysis is indebted to Barbara Reynolds’ excellent work.

Long shadow

The poem fuses together the three great themes – war, chivalry and love – within the three great traditions of Europe: the classical, the medieval, and the renaissance. The classical aspect is shown in the debt the poem owes to Virgil in particular, with many sections and moments offered as faithful homage. The medieval we see most obviously in the knightly matter and ornamentation the poem commits to throughout. The renaissance is present in the way how human passions take the center place as character motivation instead of devotion to God.

Ariosto was lucky to publish his work when he did, because the Counter-Reformation would soon crack down on renaissance romance, indexing them, banning them, even prohibiting their exportation to the Spanish colonies beyond the sea. Echoes of this attitude can even be seen in Cervantes’ Don Quixote, where the addled hero’s book collection is burned as clearly harmful to the peace of his soul. However, it is notable that Orlando Furioso is one of the books deliberately spared from the flames, because of its high excellence.

The poetry that the Counter-Reformation esteemed was to be more serious and more pious, but probably also less fun and charming. Ariosto’s plotting incredibly tight despite its complexity, retaining a satisfying internal coherence despite all the disparate elements. The poet writes with a sense of freedom and joy, with pleasing the reader as his primary motive, and caring little if at all about Christian typology or philosophical allegory. Consequently the poem stands on its own. It has depth, but it wears it all on its sleeve. “Its charm is based purely on what it is, not on what it implies.”

Orlando Furioso has ended up influencing the path taken by Western literature. Sir Walter Scott, the inventor of the modern historical novel and a great romantic on his own right, was titled “Ariosto of the North”. His own tremendously popular long-form chivalric narrative poems like Lay of the Last Minstrel are obviously inspired by the Italian master. Byron was another admirer, with Don Juan as a clear product of inspiration. We may perceive connective tissue running through Ariosto, Cervantes, Shakespeare, Scott, and Dickens, all the way to Chesterton.

Eichiiro Oda’s One Piece is a modern example, with several points of connection: human passions at the forefront of adventure that wears its heart on its sleeve; a seemingly infinite cavalcade of characters with complex interactions and continued relevance through the vast story; constant diversions and “side quests” that first appear to contradict the main pull of the story, but end up heightening it; larger than life heroes doing impossibly heroic things that reach a point of absurdity that compels a smile. Both works of high romance took (or will take) their authors decades to complete!

Maddened Orlando

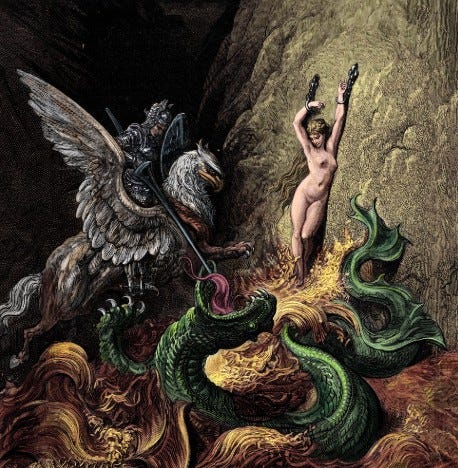

Rather than being the protagonist of the story (Ruggiero or Astolfo might fit the role better), Orlando functions more as a thematic centerpiece. Absent for large swathes of the story, he’s nevertheless the man who the reader will remember at the end. Orlando is the Italian name for Roland, Charlemagnes’ most powerful Paladin. The man is indestructible and invincible in battle. No opponent is his match. But however impervious he is to swords, Orlando is helpless in the jaws of love.

Angelica is the girl he dreams of and pursues throughout France, hopelessly and unrequitedly in love. For a long time the love Orlando feels functions as a motivating force. It drives him to adventures where he destroys villains and defeats heroic opponents. But at a crucial moment comes a collapse: Orlando finds out the love of his life has given her virginity to another man, to an African soldier, no less. This gives rise to the title of the poem: the fury, or madness, or Orlando.

The realization that the untouched purity of his beloved is now forever gone is too much for our hero to bear. The man loses his mind and becomes a bestial force of nature, running around the world causing endless havoc. In a memorable moment his horse gets tired, but the man remains tireless. He keeps on pulling the horse until the poor creature perishes in exhaustion, after which Orlando drags its sorry corpse throughout France. Thus the loftiest knight becomes the greatest brute in the face of lost chastity and extinguished hopes of love.

“ A virgin may be likened to a rose, which by thorns defended within a garden unmolested grows. With zeal a virgin should defend this prize.”

“Virginity is the morning rose which no despoiling hand has ever touched.”

“That lover has a cause to lament who falls a captive to the hair and eyes of one who in her heart, as heart as flint, conceals impurity, deceit and lies.”

“During the days you have not heard of her, she fell into the hands of twenty men or more; consider, after that, what flower then there will be left for you!’”

“What is left to her whose chastity is lost?”

The expectation of chastity, often disappointed, is found at the heart of the poem. It is a note that repeats and echoes throughout, and is told and retold in many sub-stories within the main narrative. We are told of a kingdom where unchaste women are executed. We are told of husbands who decide to test their wives’ chastity by tempting them (always to the husband’s horrified disappointment). By contrast, we are also told of ladies who rather choose to die than lose their purity.

Side by side with the esteem of female chastity the poem holds a natural acceptance of male lust and passion. We are told how it would be completely natural for our heroes to simply “take a woman” if given the opportunity. As natural “as fire burns straw.” In fact, Ariosto goes further still:

The curb of reason seldom will turn back

A lover’s ardour from its frenzied course

Where pleasure lies to hand; as from its track

A prowling bear the smell of honey lures,

Or from the jar its tongue may catch a drop,

And nothing will induce it then to stop.

So now, what reason will the knight deter

from present pleasure of the lovely maid

Whom at his mercy he holds naked there

In that convenient and lonely glade?

No memories of Bradamante stir

His heart and conscience; even if they did

(For many times sweet thoughts of her arise)

He would be mad to forgo such a prize.”

Not only is reason too weak to prevent the knight from forcibly claiming a beautiful woman in an opportune moment: we are told he would be mad to forego such a prize – so deeply contrary would it be to male nature as to constitute a type of insanity. And mind you, this is not just any character Ariosto is talking about: he is laudable Ruggiero, a main hero of the story, who ends up happily married with his chaste Bradamante. But even the exemplary groom is a man with a man’s nature.

Ariosto offers us no equivalent expectation of chastity. Rather, the message is that because men are what they are, it is only all the more crucial that women guard their chastity with redoubled effort. Along the way we are shown how even a devout hermit monk is careful make sure he does not spend time alone with an attractive woman, cognizant of his male nature. The essence of masculinity cannot be wholly altered even by religious vows, so women must be ever vigilant to guard the flower of their garden.

Men, on the other hand, he advises not to pry or to test:

“You are the only husband wise enough

Not to risk ruining your married life

By measuring the virtue of your wife.”

Love’s turmoil

The solution (which Ariosto admits is unrealistic) to the difficulties of healthy and workable love is always chastity, “a term not heard of in our century.” This is the tension at the heart of the poem: the characters want to love, but are repeatedly spurned by lack of chastity. Either it’s male lust turning love into fornication, or it’s female lack of purity destroying the dream of love and marriage – even to the point of causing maddening grief to the titular hero.

Another obstacle in love’s path is principle. This is most poignantly depicted in Ruggiero. Whereas his earlier desire to forcibly enjoy a girl was not treated as a crucial breach of principle, going against his word of honor is. Renaissance ethos shows us how a man’s lack of chastity need not destroy his honor. It is treated as nothing when compared to breaking his word, being disloyal to his lord, or thankless towards a benefactor.

Indeed, the tension between love and integrity forms an excruciating test for Ruggiero near the end of the story. First his marriage is delayed by the necessity of fulfilling his duty to his moslem king. The Christian woman he loves remains on the opposite side of the war.

“Love of his bride was strong, and of her beauty,

But stronger still his honour and his duty.”

Later he would be free to marry, but is thrown in prison by a devious queen. He is liberated by a kind man to whom he gives his promise to help in whatever the man seeks to accomplish. The tragedy is that his savior too is in love with Bradamante, and asks for Ruggiero’s help in marrying her. The situation is unbearable. Ruggiero’s duty compels him to give away his bride to his savior. But love says no.

Love and conscience are two of the strongest forces in the human heart. When they cannot be harnessed to the same carriage the result is chaotic. When they pull in two opposite directions, the result is a heart ripped apart.

Wandering alone in starvation, and pining away with the impossible situation, Ruggiero comes close to suicide.

“To win my bride for you – a role

Which was equivalent to asking for

The heart out of my body or my soul;

For I could live without

My soul as soon as live without my wife

And while I live, of this there is no doubt,

She cannot be your lawful wedded wife.”

But his savior is a good man, who after learning about what has happened, relinquishes his claim. He deeply admires Ruggiero’s honor and principle.

“You are much worthier of her than I.

It’s true I love her for her martial fame,

But I do not intend, like you, to die,

If someone else can prove a better claim.

Do not sacrifice your life,

Not thus do I desire to win a wife.”

After all the horrors of faithlessness and impurity we have witnessed amid the epic, Ariosto leaves us with the satisfaction of witnessing a happy marriage, as any Western writer of comedy should. It is both the suitors’ willingness to sacrifice, and the bride and groom’s patience and shared nobility of character that unbolt the doors of happiness.

The shoals are manifold and the path rocky, curbed by purity and principle. But Ariosto’s romantic vision never gives up on the treasure at the end of the rainbow – and doesn’t permit us do so either.

Join The Discarded Vision to explore truth in literature and strength in faith!