I want to share with you a splash of wild, romantic, Chestertonian ideas from his essays, alongside some applications and interpretations of my own. Perhaps you are already asking, why the minotaur? Because that’s what we are. Not to worry, all shall be explained.

On happiness

The human heart is a fragile thing, and sometimes it will be broken, or at least receive a painful hit. Animals get to enjoy a steady, stupid happiness, which many may envy. But if we truly wanted to have the same, we would first need to get rid of our human heart. Indeed, perhaps that is one of the goals of the trans-humanists.

Fortunately, it is really not so important for us to be happy than it is to be jolly. An abstracted philosopher may have happiness as his target. But the Saints are jolly. Life isn’t about maintaining a stable level pleasure and enjoyment, but about remaining receptive to the powers of laughter and surprise. Underlying this is the religious desire for striking holidays like Christmas, and the tendency of philosophers to dislike them, because such wild interruptions go against the principle of stoic steadiness and stability.

As Chesterton says, religion is not interested in man’s happiness, but in whether he is still alive – whether he still laughs when he is tickled, or weeps at a broken heart.

On modern art

It is probably true that in the past there were many artists who claimed to be great even though they were unsuccessful. But they definitely didn’t claim to be great artists because they were unsuccessful. That is a phenomenon unique to our day, which holds a constant bias against normalcy and common sense.

On the sexes

The battle between the sexes is like a battle between knives and forks. For the purposes of eating, both are equally important, but nobody ever claimed that knives make good forks. The difference isn’t merely one of function, as Chesterton maintains that if knives and forks had souls, they too would be of a different shape, just like their bodies. Of course, in the Aristotelian sense this is very much the case.

One thing that makes the female soul peculiar is its tragic desire for beauty. Unlike with men, this keen desire for seeing beauty around them is never an affectation with women. It is truly heartfelt.

“Women care about small things even when they are tortured by the greatest things. Even in their greatest sorrows and agonies they keep calling upon beauty.”

Chesterton believes this has something to do with the deepest depths of female nature and purpose, with the fact that they are the priestesses of the nurture of children, and the sacred keepers of the homely hearth.

The difference is also noticeable in the way the sexes dress. For men, clothes are always a uniform, even when they are extravagant. For women, clothes express their desire to be singled out and feel special. It is extremely embarrassing for a woman at a party to find that another woman has the same dress as her. For a man it is a great comfort to note that he is dressed in exactly the same way as everybody else.

Feminism fundamentally disrupts the balance of these sexual relations. Sometimes the matter at hand may appear small (such as taking off your hat before a woman), but ostensibly small things can reach incredibly deep – hide a whole iceberg beneath the waves.

“Wear your hat before a lady, and you have said that she is not a lady; you have destroyed the whole structure of civilization on which she stands…. No one will ever begin to understand men and women till he understands this fact: that every man must be a man, but every woman must be a lady.”

The greatest irony of feminism is that underlying it is a deeply masculine impulse, and its triumph signifies the victory of the male point of view over the female. Through feminism, cold male logic is permitted to vanquish female common sense and practicality.

Ever since the grottoes of cave-men, these two points of view have been waging a friendly war, which has always remained in the heart of the dangerous romance called marriage. In this struggle the man has always insisted on the importance of abstractions, principles, logic, intellectual fairness, and the rules of games.

In contrast, the woman’s point of view has always said that the outcome is the only real test, that happiness and unhappiness can never be argued with, that the only good rule is the rule of thumb, and, above all, that the one truly worthy thing a man ever achieves is the actual living he makes, the field he ploughs – and (crushingly for the male spirit) all the other things he enjoys, from politics to philosophy, are just the games of a school-boy.

The stark irony is that feminism has raised the white flag for the pragmatic female point of view, and embraced fundamentally masculine logic-chopping, and the abstract, decidedly non-practical viewpoint centered around the ideals of liberty and equality.

“The feminists have surrendered the fortress of their sex. They have come into our camp in complete surrender, admitting that we men have always been right and the women always wrong. That we were right on insisting on the abstractions, and that they were wrong in laughing at them. The feminist movement is a surrender to the masculine intelligence.”

On vulgarity

It is not funny to see leaves falling, or to see the sun going down. But it is hilarious to see a man slip on a banana peel. All practical jokes are ultimately theological, because they relate to the Dual Nature of Man. They point to the reality that man is at the same time superior to all things around him and constantly at their mercy.

This underlying theology also explains why we laugh at foreigners.

“Nobody laughs at things that are completely foreign; nobody laughs at a palm-tree. But it is funny the see the familiar image of God disguised behind the black beard of a Frenchman or the black face of a Negro.”

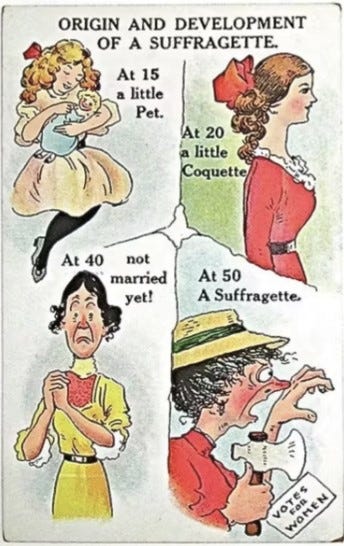

The vulgar man’s insensitive jokes are a much better predictor of reality than scientific studies or prognostications. For example, vulgar folk always depicted early feminists as ugly women, “fat, in spectacles, with bulging clothes, and generally falling off a bicycle.” In fact, the leaders of so called female emancipation were mostly quite pretty and well-dressed. However, the vulgar were still correct, because at the heart of the feminist movement there was always a spirit of indifference to female dignity, a willingness for women to become grotesque.

The vulgar man’s instinctive observation – incorrect superficially, but correct fundamentally – was quite crucial, for “the two things that a healthy person hates most between heaven and hell are a woman who is not dignified and a man who is.”

On false devils

Nowadays, as in Chesterton’s, we are surrounded by false devils. This is essentially form of reverse idolatry. Idolatry can be instituted not only through false gods, but also through false demons, by making people fear things they need not be afraid of – climate change, meat, Trump, racism – instead of fearing spiritual corruption and cowardice.

“The Moslems say, ‘There is no God but God.’... Remember also that there is no Satan but Satan.”

On machines

Our inventions have made us too timid. “There are some things more important than peace, and one of them is the dignity of human nature.”

We must never decline from having a war just because of fear – be that fear of machine guns, of poison gas, or of atomic bombs. We are not given a spirit of fear, and we must always have some better reason for wanting peace.

“It is an awful friendship between nations that is based on both parties being too afraid of the sound of a pistol.”

But by all means, let us get rid of the nasty weapons. Man created the machines he now notices are bad for his soul and that cause him to fear. Then let him save his soul and abandon the machines.

Those who have lauded the Mutually Assured Destruction -doctrine as a keeper of peace would have earned the scorn of Chesterton. It constitutes the very reverse of the course he recommended. Instead of abandoning the machines, M.A.D. hangs them as a sword of Damocles above our heads, only inflaming the fear.

“Man is cowed into submission by his own clockwork. I would sooner be ruled by cats and dogs. I would rather have any war, no matter how long and horrible, sooner than such a horrible peace.”

On resistance

Sometimes it is necessary to oppose the state, but in those situations only active resistance can be any good. Passive resistance only makes the state apparatus work less efficiently. It leads to no change, only to a more arduous life for everybody.

“There is no excuse for any disorder which is not a rebellion.”

On realism

While it is true that some have a tendency to overrate human achievements to the point of pride, many also gain a perverse pleasure from changing the poetic into something prosaic.

The writer of a romance collects all instances of beautiful triumphs, while the realist grasps the squalid failures with equal ardor. But we must be mindful that the bias of the realist is just as extreme. And he has an easy task ahead of him.

“If you throw enough mud, some of it will stick, especially to that unfortunate creature Man, who was originally made of mud.”

A realist novel is written by stringing together all our failures and irrelevances, “all the trains we miss, all the buses we run after without catching, all the appointments that miscarry, all the invitations declined, all the infant prodigies that grow into stupid men.”

Realists connect into an artistic whole things than in nature are wholly disconnected. They are not facing life as it is, because real life is too beautiful to be faced. “No man shall see life and live.” Realists are making a special, personal selection, just like the optimist or the romantic. They hunt for all the meanness, pointlessness, frustration, humiliation.

What’s remarkable is that this not only applies to realist novels, but to modern historiography. The dominant school in academic history is equally anti-romantic, and its thankless task is to try and explain away all the great romances that have quite obviously happened.

On pride

The deepest forms of pride are unconscious. There is nobody so narrow as the man who is sure that he is broad. In fact, being sure that one is broad is itself a form of narrowness, because it reveals that one has a remarkably narrow idea of breadth.

On divorce

Somebody once wrote to Chesterton, saying they believe that indissoluble marriage is good for the great mass of mankind, but there should be allowance for some exceptions. Chesterton pointed out that there may be sensitive souls who really feel unwell when they see a policeman, and exceptional people who would be happier without a Civil Government.

“But we surely have the right to impose the State on everybody if it suits nearly everybody. And if so, we have the right to impose the Family on everybody if it suits nearly everybody.”

The problem with admitting any exceptions is that the people who come to claim them are always the ones who least deserve them. If we say that marriage is good for the common stock, but divorce is available for some particularly free and noble spirits, all the weak and selfish people will immediately jump at the chance. “At the same time the truly free and noble spirits you so wish to help will very probably (because they are free and noble) go on wrestling with their marriage.”

The real mark of dignity is humility – unwillingness to split oneself off from common humanity. After all, “All men are ordinary men. The extraordinary men are those who know it.”

On human nature

Ever since we are children, human beings with immortal souls need to be forced to be physical. Children often neglect their own bodies. They must be reminded to eat, put to sleep, and demanded to wash themselves or to dress up. Their lives are very soul-centric, living in daydreams, relying on child’s faith, and constantly meshing reality with imagination.

For the same underlying reason we come to realize man is a monster – like a centaur, a mermaid, or a minotaur. The monstrousness results from man being a disjointed creature, only partly perfect. This truth clashes with the evolutionary worldview, which claims man is morphing and moving ceaselessly from imperfection to relative perfection, changing so as to become suitable. But in fact, the immortal and mortal part of man are very distinct and always have been.

Our minds are filled with conflicting desires and inclinations – like distinct voices shouting us their commands. In order to reach a sane and stable way of life we must have the wisdom to obey some of the voices and discount others.

“You may you have a reason for making sweets or some better idea for poisoning them. The only test I know by which to judge one argument or inspiration from another is ultimately this: that all the noble necessities of man talk the language of eternity.”

Whenever we are engaging in one of the handful of tasks that are truly important, the ones that we were sent on earth to do, we behave like a being who will live forever. Men dying for their country. Men giving laws to nations. Men falling in love. Men forming families.

When dealing with the things that truly matter, we speak only in absolutes.