I have a book to recommend to anyone interested in Constantinople, late-medieval life, siege-warfare, Greek Orthodoxy, the East-West Schism, philosophical discussions on realism/nominalism/existentialism, sharp eyed observations on the dynamics between the sexes, among other things.

In 1953 the famed Finnish author Mika Waltari published one of his many historical novels, Johannes Angelos. The book was translated into English under the name Dark Angel, and you should still be able to find copies at a reasonable price. The quotations I offer here are my own translations from the original Finnish version, which I’m familiar with.

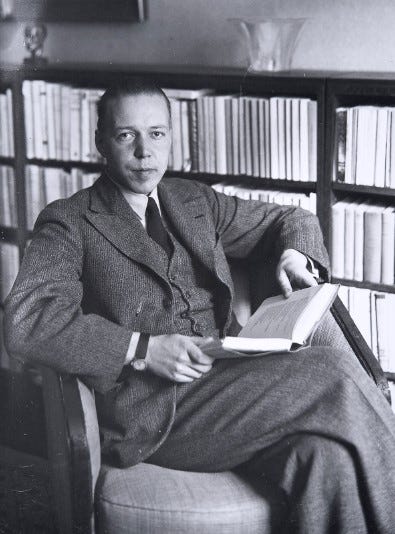

Throughout his life Waltari could generally be classified as a patriot and a conservative, increasingly so with age. Born in 1908, at 10 years old he was part of the rapturous crowd throwing flowers at the feet of General Mannerheim’s steed, when the national hero marched before his men in liberated Helsinki, having led the Whites to victory in the Finnish Civil War.

As a young man in the 1920s he was influenced by more cosmopolitan literary circles and was troubled and somewhat tainted by the general nihilism of the times. He never became a decadent or a leftist, but the experiences left their mark. In the Second World War he served in the Propaganda Division of the Finnish Army.

After the war Waltari’s popularity exploded when he began to write his grand historical novels, most famously The Egyptian, which gained a significant international readership, and in 1954 even a Hollywood film was made based on it.

Two forces form the general tenor of Waltari’s writing and thinking: a healthy patriotism / conservatism combating with more nihilistic, cynical tendencies. But as he reached middle age, a third influence began to loom over everything. He became increasingly drawn to Christianity. His later novels tend to deal with it heavily. Johannes Angelos exemplifies all the tendencies mentioned, and there is a great deal of Waltari himself in the titular protagonist.

The novel, as usual with Waltari’s historical epics, is not just an adventure story or a book about warfare. I’m aware some reviewers were disappointed with the novel, finding it ‘boring’ because the first half of the book is mostly about philosophical discussions, theological controversies, descriptions of male-female dynamics, etc. The action of war only begins to dominate the story in the second half, and even then the deeper elements never go away.

I desire to discuss two of those deeper topics here. First, the the philosophical discussion on the dawn of modernity. Second, the nature of women and the male-female dynamic.

Modernity beckons

Waltari presents the fall of Constantinople as an epoch defining or epoch ending event. The conquest of the city is the dream of the Sultan of the Ottomans, Mehmed The Conqueror, but it is not a dream like those of the ancient leaders of men. There is no romance here, no higher ideal. The Sultan conquers purely to manifest his Will. He is, indeed, beyond good and evil.

This relates to the questions the titular Johannes Angelos has been haunted by for years. He read philosophy and philosophy made him miserable, confused and conflicted. It has driven him to heterodoxy and doubt, and the man has been on a trajectory towards madness and despair.

What kind of philosophy? Essentially, the Modern mind in embryo. The teachings that have troubled Johannes are relativist, subjectivist, existentialist, anti-Aristotelian. He has lost his footing on morality, on reality, on his own existence. His mind is disturbed by confused ideas of reincarnation, illusory nature of good and evil, vanishing categories. But greatest of all, there is the temptation of centering himself purely around his own Will. This is the philosophy of the Sultan, whom Johannes has known personally. But in the end Johannes made his choice. He rejected Modern Philosophy and chose Ancient Tradition. He chose to die defending Constantinople rather than live in the Modern world.

The Sultan is his foil. He is the man who embraces modernity. He represents the rising era of the Subjective, the era of the Personal Will. This is the stuff of Protestantism, the stuff of the Enlightenment, the stuff of Liberal Democracy, the stuff of Satan. The Crescent in the flags surrounding Constantinople is to be understood the mark of the Beast.

But there is still something standing on the Sultan’s path. The Second Rome, the City of Constantine. Constantinople is now only a shadow of its ancient glory, but it still stands. Its walls are thick and its tradition deep rooted. For the new era to begin, Constantinople must fall.

Although such are the opposing forces, the case isn’t oversimplified. It’s made clear that the building blocks of the ensuing era are present in Europe as well. All the Western powers, including the Pope himself, are engaged in cynical power games, though none of them have anointed themselves to the active worship of the Will the way the Sultan has. Instead, Western leaders avow one thing and do another. Hypocrites they are, but even the ugliest hypocrisy begins to look lovely when set beside naked nihilism.

The Greeks of course are no saints themselves. Their pathological internal politicking and external double-dealing constitute a key reason for why things have become so desperate. Even while under siege by the Turks, and fighting side by side with the Venetians, the Greeks may still cry, “Sooner the Turkish turban than the Latin mitre!”

Johannes Angelos is in a unique position to perceive what is at stake and what is to come. Thus far man may have neglected God for worldly reasons, but in the future he will utterly abandon God. The material world shall be the only one for him. It will be a world of sheer utility, of unbridled machiavellianism, of cold materialism. “A world where men are dead while they still live.”

The Sultan, unlike other princes of his time, already lives by the rules of the new world. Superficially he may appear to pray and to fast and to live by the rules of Islam. But it is all for show. His behavior is really modified by nothing outside his Will. He has faith in nothing else.

Constantinople is “the utmost bulwark of the Tradition of the Ancients.” When the City falls, the new era begins. When the gate holding the future at bay is crushed, what awaits the West is “death of the spirit, life without hope, love without joy.”

The Tradition of the Ancients that Constantinople stands on is Christianity coupled with Greek wisdom. The novel describes a master engineer who gets permission to study in the imperial library, where the Greeks have jealously guarded their ancient texts. The librarian is particularly irritated because the curious engineer shows no interest in the works of the Church fathers or other religious works. He thirsts to read the books of Archimedes and Pythagoras, desiring to make practical use of their knowledge in mathematics and engineering. He is a modern kindred spirit of the Sultan himself.

Soon he comes to realize the ancients had in their hands sufficient knowledge and the skill to transform the world then and there. They could have initiated Modernity in 200-300 B.C., but “instead of using their wisdom to assert mastery over nature, they retreated to themselves, to the soul, to God.” What seems so disappointing, foolish and wasteful to the engineer, looks like a sign of great wisdom to Johannes Angelos.

Though the number crunching mind of the engineer admires certain aspects of past knowledge, for the Modern era to really take hold the wisdom of the ancients needs to pass away. Plato’s supernatural Ideas must perish. Aristotle too must be abandoned, and with him all inherent essences, as well as the strict logical categories of either-or. Right needs to mesh with wrong, truth with falsehood, good with evil – thus ceasing to be. Opposites and contrasts need to abolished and replaced with spectrums and fusions. Meaning itself is to be relativized and subjectivized, emptied out.

Such goals echo aspects of Luther, Hobbes, Marx, Sartre, and ultimately the Death of God pronounced to all hearers some four centuries later.

As you know, the Sultan was victorious and the city of Constantine fell. Modernity soon ensued. The novel makes a convincing argument that the fall of the Second Rome was a key causal factor.

Women

Conjoined with the philosophical, theological and historical discussion appears the topic of women. In recent decades Waltari has often been accused of misogyny and sexism, and it is fairly easy to understand why. “It’s easier to get tangled up with woman than to get rid of her.” Waltari offers an alarming image of women and of the male-female dynamic. He depicts women at their sweetest and most alluring, but also at their most fickle and calculating. “Deep inside every woman is like a cat. She loves to play with her lover.”

The novel at hand focuses particularly on the effect women have on men’s priorities. It is well known that women tend to act as a prime motivator in men’s lives – push them to work, to pursue a career, to get money, to get ambitious. But the novel presents a more disturbing scenario: what if the man has renounced the world and considerations of utility, and chosen faith and higher principles?

As may be guessed, the result is ever increasing tension, which pushes the man to the point of breaking. The story makes the case that women do not really understand honor. Or rather, to a woman honor means splendor. She loves it, but she can live without it if necessary. And above all, women do not really understand what principles mean for men.

To women principles are secondary, to be put below more practical matters: earning a livelihood, the bearing and welfare children, security, social standing and reputation both personal and familial, and simply getting along in society. If a woman is asked to forego the practical aspects of life for the sake of principle or honor, she will balk. Why should her husband die for a lost cause? Makes no sense. Why should faith come between him and her? How unreasonable!

Not only will she reject the higher principles herself, she will do her best to deter her man from following them whenever they threaten core utility. “Go ahead, live in the world of your conscience. But know that then you will live and die alone. In the world of living people you need to adapt to others, and compromise your principles.”

It is commonly understood that marriage is all about compromise and sacrifice. But the novel points out that often the husband isn’t only sacrificing hedonism, selfishness, free time, or general ease of life. He may well end up sacrificing his principles and perhaps even his faith. Some of the sacrifices required by marriage may damage the man’s integrity and even his hope of salvation.

This is the harsh practical reality that a woman places before Johannes Angelos. Keeping hold of your principles will make you a lonely outcast and a social failure. It is quite possible a man cannot have a wife and a family while keeping hold of high ideals and while retaining a pure conscience. Waltari presents this difficult choice in all its nakedness.