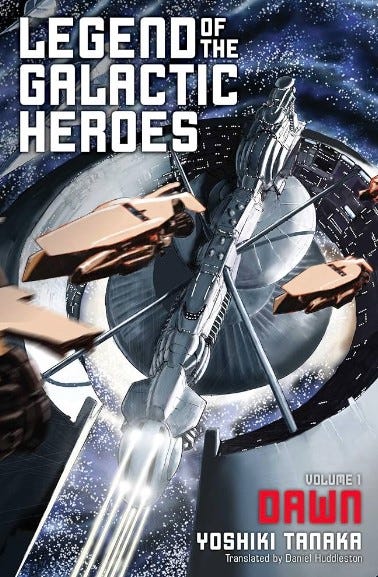

I recently finished reading Yoshiki Tanaka’s grand space opera, Legend of the Galactic Heroes (published between 1982-1987, in ten volumes). The animated series based on the novels has reached classic status, and references to its iconic black-and-silver uniforms and German nomenclature are encountered constantly.

It is a story about an decidedly German galactic empire in year 3656 AD, and about the struggle of the America-inspired multicultural republicans against the Galactic Emperor. Despite the similar sounding set-up, in many ways this is the anti-Star Wars – both in terms of ethos and in terms of content. There is no magic here, nor aliens, the republicans are not the ‘good guys’, and even the scifi aspects are mostly irrelevant. 90% of the story could just as well take place in the 19th century. LOGH is all about political philosophy, militarism, and the dynamics of Great Man history, all written in a Romantic style.

What makes the series unique is largely consequent to the fact that it is written by a Japanese man with obviously reactionary tendencies. The treatment of the opposing parties is quite even-handed, and there is no clear ‘pro-democracy’ message that an American scifi writer of the period would almost inevitably have included.

The Germans and the Americans

At the center of the events is Reinhard von Lohengramm, a rising star from the small nobility within the empire, who grasps ultimate power in his early twenties, and becomes an Alexander-esque conqueror of the world. Reinhard is presented as truly larger than life, and he surrounds himself with men almost equally great – a small cadre of incredibly talented young admirals loyal to him personally. Chief among them are the Twin Pillars, the ever likable Wolfgang Mittermeir and the always cool and aloof Oskar von Reuenthal. Their sheer talent and personal friendship form the backbone of the revitalized Imperial military.

Opposed to the Empire are the Republicans, whose most talented military leader and strategist is one Yang Wen-li. Yang is probably the most intelligent man in the galaxy, with a strange, almost inexplicable attachment to the ideals of democracy. The novels make a point of it. Multiple times the story asks why does Yang even bother fighting against an obviously competent monarchy, and keep toiling for the sake of a nasty, corrupt republic? Yang is driven by an instinctive dislike of Great Men and the great Exception they represent to the human norm.

“Regaling children with tales of ‘great men’ and ‘heroes’ is plain stupidity. It’s like telling a fine, upstanding human being to take lessons from a freak.”

After such moments of inner certitude, Yang often grows more doubtful about his ideals:

“To guard against the possibility that a wicked dictator might one day take control, we must take arms against our enlightened ruler today, for only by defeating him can we ensure the survival of democratic republican governance based on separation of powers.”

The paradox was laughable. If the institution of democracy could only be protected by toppling virtuous rulers, that made democracy itself an enemy of good governance.

In the end, even the most intelligent man in the universe cannot offer a fully satisfying answer. His ideals rest on an alarming high and optimistic perception of the capacities of the average person. Ironically, in this regard the democratic republicans are ultimately shown to be much more sentimental in their beliefs than the romantic monarchists.

Yang and his friends are generally presented as more immediately relatable and easy-going, and their underdog status makes them easy to sympathize with. They read as more American or ‘Anglo’ in their relaxed attitude, compared to the stern and decidedly German characters of the opposite side.

But it is clear where all the Romance lies. On Reinhard’s side are all the cool uniforms, the great speeches, the larger than life men, the most heart-aching friendships and shows of loyalty. In contrast, the Republic is presented as humdrum, bureaucratic, mechanistic, corrupt, incompetent, run by self-serving politicians, dull as dishwater.

The discourse is given nuance by the starting position: before Reinhard’s rise to power, the Imperial system is presented as equally corrupt (if more aesthetically pleasing) as the Republic. Led by a sensualist emperor of the old Goldenbaum dynasty, there is a sense that all vigor is spent from the system, and it takes the Caesarian figure of Reinhard to reform the Galaxy and give it new life.

Weaknesses

The greatest weaknesses of the work are twofold, one is technical and the other more fundamental. The technical problem relates to the simple craftsmanship of the story. The prose is merely workmanlike, though possibly hampered somewhat by the translation, this is hard for me to say. The plot is rarely very ingenious, and often the the pacing slows down. The ten volume story could probably have been told more effectively in something like eight parts.

Still, there are still many evocative moments and the romantic style allows the workmanlike prose to sometimes rise up and punch above its weight. And given that this is a story where the deeper, philosophical aspects are key, matters like prose and pacing become less crucial.

This is also why the second weakness is more serious. Like most science fiction, the story has a completely unserious understanding of religion. To its credit, LOGH at least gives religion a place of prominence, unlike series such as Star Trek that believe humanity can ‘grow out of religion’, and think that the topic can be simply side stepped.

But even though LOGH discusses religion, it does so with childish simplicity and superficiality. On the one hand there are off-hand references to pagan gods like Artemis on the Republican side, and Odin on the Imperial side. But it is apparent they are treated as something purely aesthetic, without any actual religious devotion. They represent flair given to names, or resonance to lines of dialogue, nothing more.

More serious is the so called Church of Terra, which is a secret society of fanatics whose unrealistic goal is to make the empty, degraded and resource poor planet Earth the center of the galaxy once more. The idea presented here is that religion is ultimately only a tool used for political purposes, or a cult which may victimize unfortunate, gullible individuals. Thus, religion is either purely aesthetic, or something strictly negative and fanatical. The presentation is both very 1980s and very Japanese.

Traditional understanding

A personal highlight of mine in the entire saga is the friendship between Reinhard von Lohengramm and Siegfried Kircheis. Their affection and devotion to each other is very convincing and expertly written, bringing to mind Achilles and Patroklos, or David and Jonathan. Siegfried is a childhood friend who grows up to become Reinhard’s ‘other half’, his moral compass and most trusted admiral and advisor.

Another highlight is the deep dislike the author has for the Republican government and its politicking. Probably the most despicable character in the story is the leader of the Republic, Job Trunicht, who is the archetypal power-hungry, manipulative politician. It is truly cathartic to see the system run and exploited by men like him ground into dust by Monarchical power.

“The suspects had taken certain precautions against the possibility of official action – destroying evidence, arming themselves with legal defenses, and buying off witnesses – but these were all predicated on a democratic republican system, and proved useless. Von Reuntahl’s administration brought the full power of the state to bear on the wrongdoers, showing not the slightest concern for democratic procedure.

Every probe, every interrogation was authorized by a single order with the governor-general’s signature – and what was more, every one was successful. These criminals who had mocked democracy were judged and punished for their wicked deeds by autocracy – an ironic turn of events indeed..”

I was somewhat worried what kind of an ending such a politically charged story would receive, but I was left feeling happy about it. It didn’t offer any conclusive answers, but felt well earned and poignant. It ended in a way that was worthy of the Tragic, Romantic ethos of the series.

Though written by a modern man with modern tendencies, the story never suffers from the problems that ail other modern books like the Song of Ice and Fire. First of all, Yoshiki Tanaka dares to think outside the modern box. He appreciates monarchical power, and understands why it so appeals to us as human beings. His anti-republican tendencies offer further icing on the cake.

Secondly, Tanaka knows that subversion is ultimately destructive to the meaning of any story: a good story has to have a coherent spirit and a consistent structure, it dares to say something, and it forms a proper arc. Many readers may complain that LOGH lacks the surprise factor that is all around Martin’s work. This is in part because the characters are treated with respect. They are not killed off merely for shock value. The story is going for thematic consistency, and proceeds towards something coherent. This ultimately allows the writer to reach a proper climax and to create a fitting ending for his story.

When an author is trying to say something about Great Man history, or about the nature of Monarchy or Republicanism – really to say anything about anything – a coherent plot, and consistent characters ultimately do the heavy lifting. They need to remain both alive enough and coherent enough for any of those higher goals of storytelling to be achieved. This basic wisdom behind the craft is why I expect The Legend of the Galactic Heroes to enjoy a more lasting success than A Song of Ice and Fire.