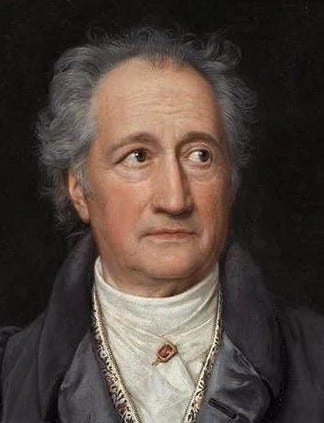

Despite his high acclaim as one of the most influential authors in Western literature – as a founding force behind both Romanticism and Neoclassicism – Goethe is an undeniably messy, uneven author, and rarely more so than in his drama of Faust – Part One (1808). Many have tried their best to see cohesion where there isn’t any, and to explain away blunders and inconsistencies as some esoteric authorial intent.

At the end many readers have been driven to ask, why is the writer of such a book considered a master of literature? Indeed, the reality is that Goethe simply didn’t know what he was doing as he wrote the work sporadically over 35 years. There was no plan, there was no consistent vision. The man himself changed, so it is natural that the book didn’t remain stable either. If there is to be any thread connecting all the disparate elements, it is the conflicted mind of the author himself. Yet the questions remain: why was it so difficult to finish? Was there something about the project itself that was untenable, no matter how much time the project was given?

Part of the problem is Goethe’s willful obscurantism, a quality in which he typifies German philosophers, many of whom were inspired by him. In fact, Goethe made his view quite clear: “The more incommensurate and elusive to understanding a work of literature is, the better it is. All attempts to make Faust rationally intelligible are vain.”

Obscurity may be seen as a fig leaf that a messy mind uses to justify the brokenness of its products, and to ward off critics by the simple claim of “you just didn’t get it” or “you weren’t supposed to get it”. Would added clarity merely expose the nakedness of the emperor?

The following attempts to make some sense of Faust and the mind of Goethe are based on David Luke’s excellent translation.

Worship of restlessness

The concept of a “Faustian spirit” was made popular by this book, where the main character Faust represents the desire for heedlessness, liberty from the limits of traditional ‘static’ morality, freedom to create his own truth and goodness, and to seek fulfillment beyond good and evil.

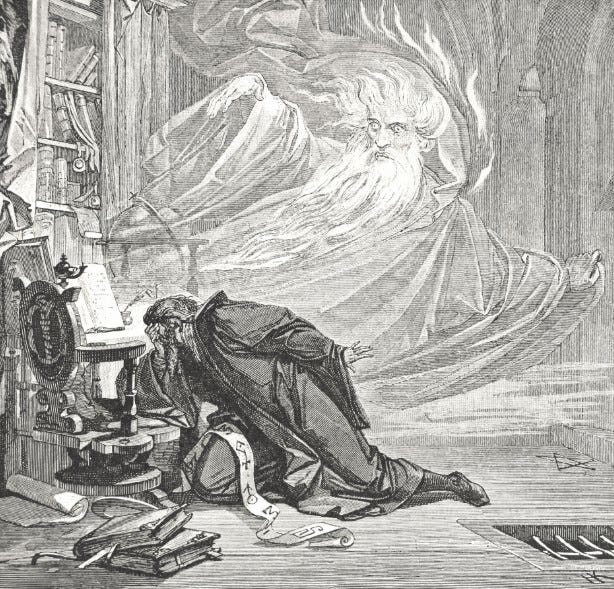

Here comes the first clash within Goethe’s structure, as the ultra-humanism he subscribes to does not mesh with the chosen legend where a man sells his soul to the devil. The story that flows naturally in Christopher Marlowe’s version is here internally conflicted. At points the “pact” with Mephistopheles feels more like a joking bet, while at others the ancient sense of gravity forces itself back in the picture. Sometimes Mephistopheles feels like just some amoral rake or a libertine friend, at others he is clearly a demon of hell. Goethe didn’t believe in the devil or in hell, but this story was impossible to tell without them. At times it seems like the author is a bit ashamed of the story he is telling, struggling to make the pieces stick together.

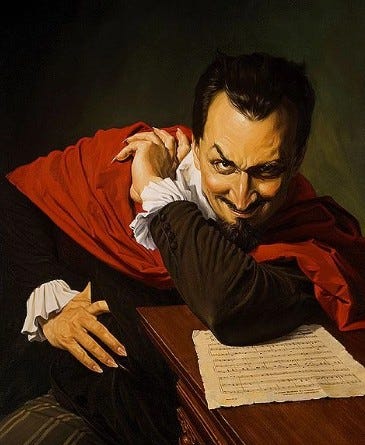

However, one idea Goethe delivers brilliantly is his depiction of the Devil as the ultimate cynic. Mephistopheles is always ironic, always amoral, always with a wry smile on his face. Above everything else he hates all that is sincere, innocent, idealistic and hopeful. Cynicism and nihilism are shown to be the same, both representing incessant negation.

If idealists like Faust fall to despair subjectively, cynics like Mephistopheles commit to despair objectively. “Objective despair” (or ostensibly objective) might indeed be an apt definition for cynicism itself. Goethe’s focus on cynicism gives us a psychologized, Petersonian rendering of the devil, but despite its limitations it is still a truthful picture. If there is one lesson a reader should take with him from this book, let it be the understanding that cynicism is a satanic impulse.

Goethe himself was by no means a cynic, and he reacted against the arid rationalism and materialism of the Enlightenment. In his reaction he went to seek solutions in pantheism, occultism, emotionalism, and humanism. Yet at the same time he couldn’t help greatly admiring Christian models like those found in Shakespeare, on indeed in the Faustus legend itself. The resulting worldview is a veritable ‘dog’s breakfast’. At times Goethe presents the world as pantheistic, with some vague “earth-spirit” as the impersonal force behind everything. But in another section we have God talking to his angels with a voice of authority – only that here He speaks like an arch-humanist, as when he answers to Mephistopheles:

Indeed, you may feel free to come and call.

You are a type I never learnt to hate;

Among the spirits who negate,

The ironic scold offends me least of all.

Man is too apt to sink into mere satisfaction,

A total standstill in his constant wish:

Therefore your company, busily devilish,

Serves well to stimulate him into action.

Goethe’s humanist conviction is that man needs no salvation, or to the degree that he does, he can save himself. God here nods at the idea, and essentially functions a spokesperson for the author himself. As long as man is active and relentless, strives and progresses, he will be saved in that he will transcend himself. An idea like the original sin would be repulsive to Goethe’s whole ethos. Indeed, it is Goethe’s humanistic optimism that the Devil so opposes. Here Christians are in fact placed in the same corner with Lucifer, with their tragic, pessimistic view of human nature.

Goethe’s hatred of binaries and absolutes is such that he wants to integrate even the Devil. Hence good and evil may be seen as simply two sides of a coin, two theses to be synthesized. Even the devil’s cynicism can work as foil, or as a whip to make man strive all the more strongly in defiance of demonic negativity. This is how God and Devil are meshed into a whole, and as a result the crucial dichotomy is no longer between good and evil, but between activity and inactivity. What we do doesn’t really matter, as long as we do it. All activity (whether good or evil, according to the dictates of traditional morality) can push us towards transcendence.

“What we call evil is just the other side of the good.”

This ethos tends to be why Goethe’s biggest fans love him so much. This is how he so influenced characters like Nietzsche and Hegel. This is why he is so central to modern culture. Goethe allows humanists to find deliverance from Natural Law and to ostensibly solve the problems caused by the abandonment of teleology. The solution offered is that the destination does not matter as long as you move. You don’t need a target, it is enough that you shoot.

Faust makes this radical liberation explicit by clearing the table philosophically. First he proceeds to curse the worldly aims of intellectual attainment, fame, honor, legacy, property, marriage, family. The list culminates in a damnation all the Christian virtues:

“I curse love’s sweet transcendent call,

My curse on faith! My curse on hope!

My curse on patience above all!”

After this act of slash-and-burn, all that’s left is the drive to self-determine, to rise beyond all rules, measures and categories. A Will to Power, one is tempted to say.

Of course all this has grave consequences to Goethe’s moral vision. His humanism pushes him to idolize striving and activity as a force that negates even goodness itself. However, the legend he is retelling is all about how rule breaking and will to power cause man to fall and be destroyed. Furthermore, the key story of Gretchen which Goethe himself invents works only to reinforce this perennial lesson by showing us the full horrors of a human fall.

It is as if Goethe the philosopher is fighting an inner battle against his better instincts as Goethe the man. Meanwhile he faces a similar conflict with the Christian legend he chose as foundation. These conflicting forces keep restricting and diverting his humanism, and push the story toward something more wholesome than the author’s philosophy would allow. The unresolved internal battle explains why the work became so fragmented, so impossible to finish, and why the author himself considered it unintelligible.

The feeling’s all there is

The story of Gretchen is the heart of the book – written earliest, it remains the most coherent and morally healthy part of the whole. To the degree that the book keeps sending messages counter to the thrust of this core, it does so to its own detriment. Here the main theme of battle between cynicism and idealism is best represented, as are the consequences of cynicism’s victory.

The story begins when Faust sees a maiden in her mid-teens walking on the street and begins to desire her. He tries to woo the girl, but she gives him the cold shoulder. Yet she can’t help but to note that it was a handsome and apparently wealthy man who so approached her. On his part, Faustus gets crazed with infatuation and demands Mephistopheles that he give him the girl.

Faust

“So virtuous, so decent, yet

A touch of sauciness as well!

Her lips so red, her cheeks so bright–

All my life I’ll not forget that sight.

It stirred my very heart to see

Her eyes cast down so modestly,

And how she put me in my place,

With so much charm and so much grace!

Mephistopheles

She’s a poor innocent little thing,

With nothing whatever to confess.

I’ve no power over her, I fear.

Faust

Why not? She’s past her fourteenth year.

Mephistopheles

You’d leave no flower on its stalk,

Pluck every flavor, every prize

That’s pleased your self-conceited eyes–

But some things have to be eschewed.

Faust

Let me tell you: either by

Tonight that sweet young thing shall lie

Between my arms, or you and I

Will have been together long enough.”

We witness how the roles reverse, and it’s the man who urges the devil to sin, and the devil in turn advises restraint and moderation. Such is the power of heedless lust and sexual allure over Faust. After initial reticence, Mephistopheles gets in line and the seduction proceeds smoothly. Gretchen soon falls for Faust and fornicates with him. The girl notes how she now finds herself on the other side of the moral fence – as one of the fallen girls she herself had previously abhorred. She wonders in anguish, how can anything be so wrong when driven by feelings of love?

This story is where traditional, static morality throws off the yoke of relativity and humanism Goethe has tried to suffocate it with. The incoherence becomes palpable. According to Goethe’s own philosophy, feeling indeed should be enough, whether in religion or in relationships. This is how Faustus explains the idea to Gretchen:

Faust

Are we not here and gazing eye to eye?

Does all this not besiege

Your mind and heart?

Oh, fill your heart right up with all of this,

And when you’re brimming over with the bliss,

Of such feeling, call it what you like!

Call it joy, or your heart, or love, or God!

I have no name for it. The feeling’s all there is.”

This outlines Goethe’s radical romanticism, based on individual feeling and removal of all rational boundaries and external forces restricting the individual will. In principle Goethe is against theology, against conceptualization, against legalism, against formal logic, against the Word of God. However, when placed face to face with the destruction of a young girl, Goethe is a good enough man to let go of his ideological prerogatives and reverts back to Logos.

Perhaps the keenest moral insight Goethe offers in the book is in pointing out the ever expanding, all-devouring nature of sin, and fornication in particular. In the following passage Gretchen’s brother Valentine lies dying, having lost a vengeful duel against his sister’s despoiler (to whom Mephistopheles gave supernatural help in the fight). He now confronts his sister, leaving nothing unsaid.

Valentine

What’s done is done, I’m sorry to say,

And things must go their usual way.

You started in secret with one man;

Soon others will come where he began,

And when a dozen have joined the queue

The whole town will be having you!

Let me tell you about disgrace:

It enters the world as a secret shame,

Born in the dark without a name,

With the hood of night about its face.

It’s something that you’ll long to kill,

But as it grows, it makes its way

Even into the light of day;

It’s bigger, but it’s ugly still!

The filthier its face has grown,

The more it must be seen and shown.

There’ll come a time, and this I know,

All decent folk will abhor you so,

You slut! That like a plague infected

Corpse you’ll be shunned.

You’ll have no gold chains or jewellery then,

Never stand in church by the altar again.

Into some dark corner may you creep

Among beggars and cripples to hide and weep;

And let God forgive you as he may –

But on earth be cursed till your dying day!

Gretchen

Oh, brother – how can I bear it – how –

Valentine

I tell you, tears won’t mend things now.

When you and your honour came to part,

That’s when you stabbed me to the heart.

As Dostoevsky notes, unrepentant sin has a consuming character. So long as a person refuses to repent, the only psychological alternative is to sin more, both to retain mental consistency and to shift attention away from the sin that had been gnawing at them previously. A hateful loop emerges, where shamefulness keeps breeding shamelessness, and shamelessness yet more shamefulness. This can be observed both at the level of an individual, and at the level of a society like ours.

The dilemma is made all the greater when sin is joined with feelings of love. As Gretchen wondered, how can something that feels so good be bad? Such moments are when we most need to keep in mind C. S. Lewis’ teaching of love’s ultimate subservience to truth and goodness.

Besides losing her virtue, self-respect, peace of mind, social-standing, and marriage prospects, Gretchen is bound to lose yet more. She becomes pregnant with Faust’s child, and because of the shame she feels (and shall be kept conscious of by society) decides to kill her child. In the 18th century, the act merited the death penalty just like any other murder. The story ends in Gretchen being taken to the gallows, without ever even learning Faust’s true name – to her he was always just some pseudonymous ‘Heinrich’.

Yet before the natural Goethian end there comes the incongruous, Christian high point – redemption. Gretchen submits to God’s judgment, asks Him to save her, to not reject her. Mephistopheles screams she is condemned. But to refute the demon’s lie, a Voice is heard ringing from above: “She is redeemed!”

Homesick heart

Time and again elements clash. Goethe builds up his humanistic philosophy only for it to be wrecked by the weight of moral reality and intruded by Christian influences. At the heart of it all lies the question of man’s teleology: what drives us, what is our purpose, where are we going? Goethe believes man’s natural drive is towards stagnation and passivity. As a post-Aristotelian modern, he is worried that we have no telos, and are thus going nowhere. This perceived weakness is what he wants to combat with his doctrine of incessant, willful striving. But again, in his writing he can’t help but allude to the truth that lies buried in his heart,

Faust

My old childhood joys relieved

My homesick heart – this I confess.

But now I curse all flattering spells

That tempt our souls with consolation,

All that beguilingly compels

Us to endure earth’s tribulation!

Faust (and Goethe through him) is pushed to confess there lies a homesickness in his heart. He immediately attacks the thought and denigrates it as beguiling flattery and tempting consolation. But surely this is incoherent. Though there is a certain sweetness to homesickness, obviously it is not a force towards stagnation.

To feel homesick is to feel something something both bitter and sweet – to understand that there is somewhere you want to move toward, a place you belong in, want to find and return to. It is a bitter feeling in that something very good lies beyond you now, yet sweet because it shows you indeed have a home, even if you don’t quite know how and when you’ll get there.

Christian thinkers would affirm that this cosmic homesickness is the healthy driver for human striving and movement. We are not to become self-sufficient Übermenschen through pride, but to find our home through humility. The joys and consolations offered by our journey homeward are not there to stagnate us, but to guide us and to keep us nourished on the way.

The abandonment of settled teleology in Western philosophy led Goethe astray. Although he perceived the yearning for home in the heart of man, he was quick to discount it. Indeed, so stubborn was Goethe in his humanism that he was willing to pool 35 years in an incongruous project where his diseased ideas kept fighting against his healthy heart.

Join the effort to regain abandoned wisdom!