The Divine Comedy is one of those works one can devote a lifetime to. A poem of infinite depth. On the other hand, Dante has been called one of the more direct and approachable poets, and one of the most easily translatable. This is partly because of the of the traditional allegorical form he uses, and partly because his poetry is based on a flow of universal ideas.

In addition, Dante wrote in medieval Italy, in an integrated European culture, where all parts of Christendom shared the same general thoughts and beliefs he wrote about. While being enmeshed in Florentine politics, nevertheless he was fundamentally a European man, a man of Christendom. He wrote when Europe was still one. This makes Dante a universal poet in the highest sense.

By contrast, though equally universal in his way, Shakespeare is much more difficult for foreigners to understand and virtually impossible to satisfyingly translate. So much is culturally determined, so much is individual, so much is based on the particular characteristics of the English language in general, and Shakespeare’s English in particular.

What makes Dante a challenge is not so much the poetry, but the fact that the gulf between the Modern and the Medieval worlds separates us from him. Shakespeare is already on our side of the gulf, though he still retains some ties to the Old. The upshot is that the greatest difficulty with Dante is not to understand the poetry (filled with obscure allusions as it is), but to understand the way the poet looks at the world.

Vertical axis

In his essay on Dante, T. S. Eliot argues that the mark of real poetry is that it can communicate before being understood. This is the secret behind Dante’s success and appeal in the modern world, despite modern man having an ever diminishing understanding of the things Dante is talking about.

In fact, Eliot argues Dante is the ideal model for all modern poets. Firstly, his method is applicable to any language – his images are universal, his language poignant but unassuming in its directness, and not overly bound by linguistic forms. Dante is a safer model for an English writer than any of the English poets, because even if you imitate Dante and fail, you only end up sounding bland. But if you unsuccessfully imitate a poet like Shakespeare or Tennyson, you will sound horrid. All the out of tune particularities and mannerisms of style will destroy you. But Dante doesn’t really come with such baggage.

Secondly, Dante uses the now underappreciated method of allegory as the foundation for his work. By their nature, allegories push the poet towards simplicity and make the images used very clear and precise. In addition, they make the appreciation of the poem easier, because with successful allegories it is not necessary to understand the meaning before being able to enjoy the poetry. Rather, because we enjoy the beauty of the poem, we feel motivated to find out the meaning of the allegory.

Thirdly, the Divine Comedy includes the whole vertical scale of human emotion, from the sublimest heights to the most abject lows. Not only does Dante include the normal emotions familiar to us from daily life, but he climbs and crawls to the extremes at both ends. In particular, Eliot believes the last canto of Paradiso to be the highest pinnacle of poetry ever reached by man. But whether high or low, no state of mind is left without powerful depiction in the poem. Furthermore, everything is integrated logically into a pattern of layers from the depths of the Inferno to the Empyrean bliss in the Highest Heaven – all with coherence and unity. In a special way, the Divine Comedy forms a logical whole, and to really understand any part of it, you must understand it all.

If Shakespeare includes all the width of human experience, Dante includes all its depth and height. By placing the two greatest poets together, you receive the complete three dimensional image of our human predicament.

Your will is our peace

Simply put, Dante’s worldview is the Medieval, Catholic worldview. This obviously opens a wide gulf between the poem and a modern, secular reader. On the other hand, the traditional Catholic worldview is so clear and objective that in some ways it makes the entry easier: you don’t have a moving target. You are entering something incredibly solid, grounded and logical.

Being a modern Catholic familiar with Aquinas and Aristotle will certainly help the reader in accessing the world the poem depicts. Yet at the same time it is obvious that all kinds of people have enjoyed the poem, or aspects of it. But the question is, do you have to be a Catholic or a Medievalist to really understand the work?

Here Eliot draws a distinction between philosophical belief and poetical assent. As a reader of a poem, you can assent to the worldview without coming to believe it yourself. It can be seen as a form of suspending your disbelief – only going even further than that: not only do you suspend your disbelief, you actually simulate a kind of belief or at least acceptance.

In the case of the Divine Comedy, something even deeper is happening. You are not really assenting to Dante’s worldview. You are assenting to a worldview Dante himself had assented to. The poem is the result of his assent, and you assent because he did. At the foundation of the poem lies not an individual choice of weltanschauung, but a humble submission to Truth.

It has long been popular to preach about the death of the author, about how texts should simply exist in themselves, floating in the air, without regard to the author’s beliefs or motives. Eliot does not agree. In his view although there is certainly a distinction between a poem and its author’s beliefs, the two are interconnected. What it comes down to is the simple notion that the poet needs to believe what he says. After all, that is the most basic element of all authenticity.

But how should we regard the poet’s beliefs? Need we share them in order to understand his poem? This is a difficult question. Technically speaking the answer would be no. It is technically true we could analyze the text from an objective standpoint, as outside observers.

On the other hand, doesn’t a full understanding naturally lead to full belief? Are we not normally convinced that it does, when we discuss any topic we care about? Surely the other person would begin to agree with us if only they fully understood the matter? Wouldn’t the same be true with Dante and his theologically charged poem?

In the end, this discussion is merely academic, because in practice there cannot exist any purely literary appreciation disconnected from other factors. In fact, we are so constituted as to gain increased enjoyment from authors whose beliefs we share. We like people whom we agree with.

Consequently, there really is no “pure poetry” or “pure literature”, neither from the point of view of its writer nor of its reader. A plethora of things completely unrelated to the abstract concept of “Art” will always enter the picture and influence the creation and the reception – be that politics, philosophy, individual quirks, moods, life experiences, or matters of Faith.

Worms born to form angelic butterflies

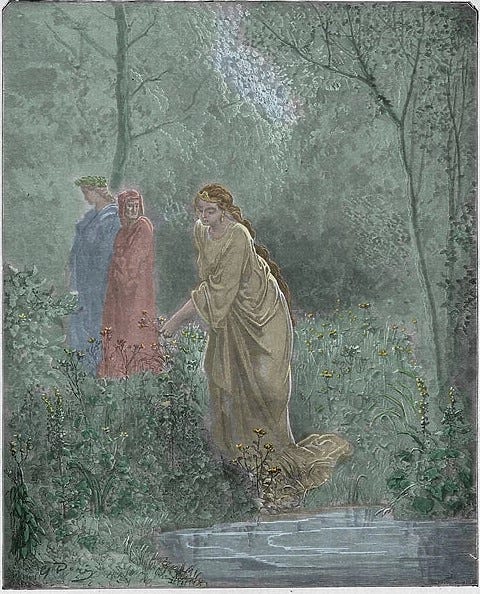

I will end by sharing some of the major lessons I learned from Dante as I walked with him through the long and winding path, beginning utterly lost in a shadowed forest, and ending as an awestruck witness to the highest beatitudes.

In part, the task of the Divine Comedy is to continue the providential story of Rome from where Dante’s master Virgil left it off in the Aeneid. Dante describes later stages in Rome’s divine mission and purpose. The Pax Romana inaugurated by Augustus was something Virgil was able to predict but did not live to witness. For Dante it was proven history, justly praised.

When Virgil was alive, Jesus hadn’t yet come, though the Incarnation was something the poet likewise prophesied. From his vantage point in the 14th century, Dante sees the crucifixion as the moment when Rome too was sanctified, and not only in the general but in a special sense. After all, it was Emperor Tiberius’s judgment (through his representative Pontius Pilate) that sentenced Jesus to death. Consequently, the redemption that ensued from the sacrifice also sanctified Roman law and imperial rule.

Three centuries later the circle that opened in the beginning of the Aeneid was finally closed, when Constantine moved the capital of the Empire to Constantinople – Rome returned to Troy.

The greatest of all miracles of Christianity that we can witness is the conversion of the pagan world to Christ.

Dante’s worldview and theology are fundamentally Thomistic and Aristotelian. Dante gives direct homage to both men. Thomas has a place as one of his questioners on his path towards Heaven. Aristotle he has logically placed in Limbo among other virtuous Pagans, but has given him a place of prominence: Aristotle is ‘the master of the men who know’: superior to both Plato and Socrates.

Cato the Younger breaks the internal logic of the poem. He is a man who committed suicide, was a pagan, and opposed Caesar. All three crimes have earned men punishments in the Inferno. Even if we counted him as a virtuous pagan despite being a suicide and an opponent of Caesar, surely his place ought to still be in Limbo with Aristotle, Virgil, and others.

Yet he is in Purgatory. Why should this be? It is one of the great mysteries of the poem. I presume it is meant to signify the mysteriousness of God’s providence. We can never fully understand it – to our eyes it will often seem contradictory and unfair. But as we trust Him, we must humbly accept that His power, judgment, and prerogative are high above our understanding.

Nature is God’s daughter. Human art is His granddaughter. This general idea is developed by Tolkien in his theory of sub-creation. Relatedly, Dante points out that “God and Nature are never defective in what is necessary.”

Nature forms our bodily constitution, our talents and inherited traits. This happens procedurally, according to the rhythms and patterns of created Nature. But our souls God creates directly and individually in each and every case, giving us Free Will unbound from the natural patterns. Thus, each child of man conceived is also a direct and deliberate act of wonder straight from the hand of the Lord.

Aside from being a perversity and a clear violation of God’s law, sodomy has a philosophical significance: it denies, twists, ignores, or obfuscates Nature’s inherent goodness.

Readers tend to vividly remember Judas, Brutus and Cassius in the mouth of Satan in the lowest circle of Hell. Their placement signifies Judas’ betrayal of the greatest spiritual power, and Brutus’ and Cassius’ betrayal of the greatest temporal power. Modern and especially English readers often have difficulty with Brutus and Cassius, partly because of all the republicanism that has affected modern thinking, and partly because Shakespeare has painted such a noble picture of Brutus in his play on Caesar. The pit of the Inferno is a place where Shakespeare’s and Dante’s visions clash.

Dante also places many romantic heroes and heroines in Hell, and after meeting them we cannot but be convinced that they have earned it. Here is referenced the Arthurian tradition of courtly love. Dante shows us how the attractive romance of Lancelot and Guinevere has led souls straight to the second circle. Observing this forces the reader to reconsider love stories and the nature of love, particularly when involving aversion to responsibility. By contrast, Dante’s own conception of love is rational and morally noble, personified in Beatrice.

Submission to evil, even under harsh pressure and coercion, will always tarnish you. Though coercion will reduce your responsibility, it will not wholly remove it. Submitting to coercion always means involvement with ‘lesser evils’. This dynamic in part explains the power of principled sacrifice and martyrdom.

Out of all the great epic poems, the Divine Comedy is really the only comedy. The only one with a genuinely happy ending without reservations. This makes it the first fully Western, fully Christian epic, as comedy is the spirit of Christendom.

Dante’s incredibly high view of Mary inspired me to pray the Rosary for the first time in my life. The first line of the last canto of the whole Comedy keeps on haunting me: “Virgin mother, daughter of your Son.”