In Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra the audience is presented with a study of manhood and of what it means to be Roman. I will here offer a few insights on how one man fell to abject disgrace and the other rose to the summit of greatness.

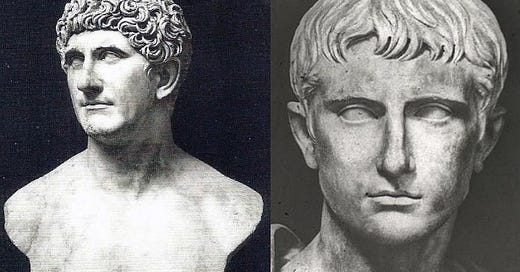

Mark Antony

Antony is the swashbuckling hero, the man’s man and the womanizer. He’s loved by his men, he’s a man of personal courage, a warrior, an inspiring leader of men. He’s also perhaps the greatest example in history of man failing and falling into disgrace because he allows his genitals to do the thinking.

Take but good note, and you shall see in him.

The triple pillar of the world transform'd

Into a strumpet's fool: behold and see.

Cleopatra had caught into her nets many great Romans before Antony, and the play constantly references her witch-like charms. We can also hear an echo of her in Virgil’s depiction of Dido. But where Aeneas and Julius Caesar succeed in disentangling themselves from the charms of an African queen, Antony loses everything. Thus he has become a cautionary example for all men ever since.

There is something pathetic in Antony’s fall, but there is also something grand in his rise. Of old the right hand of Julius Caesar, the vanquisher of his great friend’s betrayers, and now an equal with the young Caesar. Antony is the man who you call on when you need to win bigly. As Caesar does in the beginning, when he needs to have the young Pompey dealt with.

In terms of socio-sexual hierarchy Antony would be considered a classic alpha. Loved by men and women alike, jealous of his authority. He’s funny, charismatic, generous with his gifts, good company, and emotive in his interactions. He’s an open man and relatively easy to read – and to manipulate. Both Caesar and Cleopatra are able to play him, and much of his behavior ends up being in response to them rather than driven by his own prerogative.

As a Roman he clearly represents Mars, an embodiment of the old martial virtues. But Rome has two sides – love and war, Venus and Mars. With Mars Antony is in his element, but when faced by Venus he becomes a plaything and a fool. At Actium he loses sight even of the most basic principles of war, and runs like a child or a simpleton after the hysterical Cleopatra, dooming all.

We should also remember that Caesar is of Venus’ lineage as a member of the Julian family. He too is an opponent Antony cannot match, and is even mystified by. Antony rants how Caesar is only a boy and a coward, no real warrior. He scorns him as but Fortune’s favorite, great only in luck, not as a man.

To him again: tell him he wears the rose

Of youth upon him; from which the world should note

Something particular: his coin, ships, legions,

May be a coward's; whose ministers would prevail

Under the service of a child as soon

As i' the command of Caesar

Octavius Caesar

Caesar forms the background against which the ruinous passions of Antony and Cleopatra are set. He is cool, ruthless, rational, driven, measured, stoical. Caesar comes to represent Rome itself, constituting a hard foil to the effeminate forces that are corrupting great Antony. What is happening to the great general is exactly what true Romans had always been concerned about in the Greek influence on Rome, and more broadly in the negative, diassembling influence the feminine can have on the masculine.

Despite all the scorn Antony can offer, in fact Caesar is a masculine man, but in a distinctly different way. He represents cold manhood against Antony’s hot. Caesar obviously loves his sister, but is not unwilling to use her in politics, to assure Antony’s loyalty. When others engage in revelry, he keeps sure not to get drunk and lose his wits. By current parlance we might consider him a sigma as opposed to Antony’s alpha.

What makes Caesar truly remarkable is that there is no sense of overreach or hubris in him, like in Shakespeare’s other ambitious men. We witness a fundamental sense of competence and measured action. Readers tend to describe Octavius as a cold, ruthless man who always succeeds and is ‘above it all’, finding him unrelatable. But perhaps his secret is exactly that – this is a man who truly is above it all.

But all his coolness and competence does not make him into a robot or a psychopath. He truly values others, even his opponents. Caesar knows how great a leader Antony is and recognizes he needs him against Pompey. He’s even willing give the sister he dearly loves to Antony in marriage, to solidify the relationship. Furthermore, when the play is reaching its culmination, Caesar hears news of Antony’s death, and he weeps. Caesar is touched.

The breaking of so great a thing should make

A greater crack...

Look you sad, friends?

The gods rebuke me, but it is tidings

To wash the eyes of kings.

When ambition raises him to heights too near to the sun for other men, Caesar never loses his wings. He is the great one who never fell. As a man remarkably young, he won the world and went on to rule for 41 years, generally loved and practically unopposed, constituting a new era for the world. Rome’s first emperor was also her greatest.

We must note that other characters in the play can still treat his name as a name, though prestigious one. We can no longer do so. To us the name Caesar has become the term for authority itself. Kaiser, Tsar, Keisari. In this sense we may say that Octavius realized the grand title of Divus Augustus. He rises above other mortals like a Homeric hero. Godlike son of Aeneas, son of Venus, son of Jupiter.